Few would have expected filmmaker Wes Anderson — known for such quirky live-action fare as Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and The Grand Budapest Hotel — would become a respected fixture of stop-motion animation. Having proven he could cross over from live-action with 2009’s hit stop-motion feature Fantastic Mr. Fox, Anderson is back to deliver an ambitious original tale told with puppets in Fox Searchlight’s, Isle of Dogs, playing in limited release as of March 23 and due to screen nationwide starting April 6.

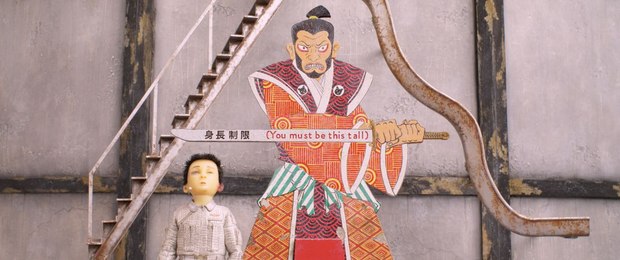

Isle of Dogs follows Atari Kobayashi, the 12-year-old ward of the mayor of Megasaki City, who goes in search of his pet, Spots, after the city exiles all dogs to a vast garbage dump to mitigate an outbreak of dog flu. Anderson directs from his own screenplay, based on a story by Anderson, Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman and Kunichi Nomura. Anderson assembled an all-star voice cast that includes Bryan Cranston, Edward Norton, Bob Balaban, Bill Murray, Scarlett Johansson, Jeff Goldblum, Frances McDormand, F. Murray Abraham, Yoko Ono and Tilda Swinton.

The movie reunited Anderson with many members of the animation crew from Fantastic Mr. Fox, including animation director Mark Waring, who admits reading the script for the first time was exciting and frightening at the same time. “It was just like Wes had written a story and hadn’t even thought about how we would do it; he just knew it was going to happen, and then sort of handed it over to me and the team,” he says. “The biggest challenge was just overcoming all of those hurdles, to try and work out the nuances of how to make sushi, or how do we do a Kabuki theater sequence.”

Waring says Fantastic Mr. Fox offered a starting point for the visuals, which were discussed extensively before production began on Isle of Dogs. “Wes wanted it to be similar but it’s obviously a very different film,” he notes. “He wanted to make sure that it was a very handcrafted film, that had all those hallmarks of a stop-frame film.”

According to Waring, Anderson referenced many of Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa’s 1960s films, such as High and Low and The Bad Sleep Well, for human performances. “It’s the way that the actors are very stoic,” the animation director explains. “There’s not a lot of outward emotion, but when it does come, it comes in bursts, and that’s something he wanted to build into this film.” The result slightly de-emphasized the humans, putting more attention on the dogs.

Anderson was hands-on in casting animators for certain sequences, much in the way he casts actors for any of his films. “There are certain favorites I suppose that Wes has, sort of like lead actors in terms of animation,” Waring described. “He knows a certain animator will do a certain thing for him…some animators are very good at intricate personal stuff, others are broader and they like the big action sequences.”

Waring says the crew on the film is used to Anderson’s unique way of working from afar, communicating through email and what the crew calls LAVs, for live-action videos, in which he’d act out his ideas for the animators to follow. He admits the idea sounds strange, but it works because Anderson stays on top of every element.

Anderson will send a LAV that shows the animator the nuances he’s going for in a specific shot, supplementing the actor’s voice performance. The result for Anderson is similar to directing in live-action. “If he’s standing in front of an actor asking them to do it a certain way, he can do that with an animator by the videos showing himself expressing and following those lines to give that little nuanced eyebrow raise or a slight smile as he’s saying a line,” Waring notes. “It’s a really good, strong guide, so when we animate we’ve got a path to follow.”

Beyond that direction, however, Anderson gives the animators a lot of leeway to find their own rhythms in a scene. Waring adds, “It’s almost like music. It was something that he was trying to instill in us, to listen to the timing and the beats.”

Animating dogs that act like dogs is a whole skill in itself. Waring says the decision was made early on not to anthropomorphize the dog characters or have them do human-looking things that dogs do not naturally do, aside from speaking, of course. References included movies like Disney’s 101 Dalmatians, as well as extensive video reference of real dogs.

“We built up a database, sort of like an animation bible, I suppose, of all that reference,” says Waring. “We tested the puppets quite a lot before we got anywhere near shooting to find out if we could make these dogs do what dogs do. Can they sit down? Can they stand up? Can they scratch their head?”

Once tests had Anderson’s approval, they were incorporated into an impromptu animation style for the movie. Waring cites as an example Anderson’s preference for the dogs to move quickly when they sit or walk, which was built into the animation. “It’s an ongoing process and you feed off what Wes likes,” he continues.

One of the big challenges in animating animal characters is fur. Not animating the fur to move naturally makes the characters look frozen, but it’s also preferable to avoid the chatter of the hair randomly moving as the animators change a puppet’s pose. “You have to almost animate the fur frame by frame,” Waring explains. “We put products in it like hair gel and hairspray and stuff like that to control it. But you ended up moving clumps around left and right a little bit to actually give the sense that there’s some external source giving it life.”

In animating the dogs’ dialog, they decided to articulate the canine puppets’ mouths instead of using 3D-printed replacement faces. The human characters used replacement faces, but Anderson again wanted something different and found it in limiting expressions and faster transitions. Notes Waring, “(It’s) almost a mask-like quality, expressions popping literally from one frame to another, rather than having a smooth transition.”

The palette of phonetic faces available to animators was limited to 13 or 15 shapes for main human characters and five or six for background or secondary characters. “It was deliberately styled to have a certain, say, roughness to it — but it’s more nuanced than that,” he says. “Every single face, every single mouth was hand sculpted by a sculptor and then it was molded and then it was hand painted. All of that work again gave it an inherent crafted feel.”

Waring describes how animation testing began toward the end of 2015, with animation work going through 2016 and most of 2017 to finish the film and the surrounding promotional items. Around 27 animators and 10 assistants worked on the film, with at some points as many as 50 shooting units going at one time. He adds that he’s proud of the hard work and research that went into creating the final result. “We achieved all of those things that I thought, in reading the script, ‘I got no idea how we do that.’ But we did it.”

Tom McLean has been writing for years about animation from a secret base in Los Angeles.

Tom McLean has been writing for years about animation from a secret base in Los Angeles.