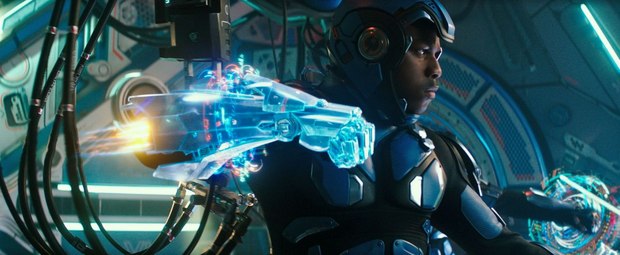

Jaegers and Kaiju Battle Once More in ‘Pacific Rim Uprising’

Overall VFX supervisor Peter Chiang talks previs, techvis, drones and Chinese sound stages on Steven DeKnight’s sequel to Guillermo del Toro’s 2013 sci-adventure romp.

Pacific Rim Uprising hits theatres today, Universal Pictures, Legendary Pictures and director Steven DeKnight’s campy, often funny action-packed sequel to Pacific Rim, Guillermo del Toro’s 2013 sci-fi adventure romp that introduced film audiences around the world to the VFX-driven spectacle of giant robot – kaiju hand-to-hand combat. Set ten years after the final battles of first film’s war between 250 feet tall, human piloted robot warriors known as Jaegers and the alien engineered giant Kaiju monsters rising from deep beneath the Pacific Ocean, Pacific Rim Uprising pits two scientific geniuses, once colleagues, against one another, with a fiercely driven Chinese mega-corporate CEO and a new group of pilots thrown in, who all defy great odds to heroically save humanity once again. Phew.

Overall VFX supervisor Peter Chiang managed an ensemble of visualization and visual effects studios that produced almost 1600 VFX shots, including newly designed Jaegers and Kaiju monsters as well as an enormous number of robot-monster battles and massive environmental destruction. AWN had a chance to speak with Chiang about his work on the film, including the extensive use of previs as well as live-action shots to give the CG animation a more real-world physically grounded look. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

AWN: When did you first come onto the film?

Peter Chiang: I joined the project quite late, literally two weeks before the start of principal photography. There was a budgetary move towards trying to make the numbers work because obviously, with all things these days, the film was greenlit, and then the appetite [for visual effects] always gets bigger than the actual budget. I took over from a chap named Jim Berney. They’d already done a lot of previs with The Third Floor, Halon and an Australian company, Day for Nite, under Andreas Hikel. I think he’s known by his colleagues as “Chop.” These three companies were working away on various sequences.

The production already had a number of houses in place to do the work, but because of Brexit and the dollar gaining so much strength against the pound, everything in the UK became that much cheaper. That gave the UK an advantage over some of the American companies where the work was supposed to go to. ILM I think was down to do some of the work. I think Sony was as well as Method. But when the pound became much stronger, as with all films these days, they [the producers] chase the rebate…they chase the exchange rate to maximize the dollars in getting images on the screen. [That meant] DNeg became a viable option as the principal house.

I was asked to supervise the show and became overall supervisor. I flew straight to Australia and met with Steven [DeKnight, the film’s director] and the team. I’d worked with Dan Mindel [the film’s director of photography] before. It’s the first time I’d worked with the production designer, Stefan Dechant. I went with my VFX producer, Theresa Corrao, who I also was working with for the first time. It’s always good to have an independent [visual effects] producer on so there’s no conflict of interest.

When I arrived, there was a lot of talk about how some sequences needed just a little bit more polish. First of all, I obviously didn’t want to upset the way in which things were being done. They’d already made a lot of decisions about how to shoot certain things. My attitude was very much one of trying to fit in, learning where the problems were and trying to help those areas.

One of the main areas was action sequences. I immediately started to storyboard them, come up with ideas about how I saw things…coming in with fresh eyes. Steven embraced that, because immediately, I could see he really liked some of my ideas. It was a process of, first, presenting to Steven and then presenting to Legendary, making sure they were happy with changes that affected production.

Steven had pointed out that Guillermo [del Toro, who wrote and produced Pacific Rim] staged most of his action at night, with rain and obviously, lighting. There are a lot of CG cheats you can do [in a night scene] because you’re can create any light source you like and justify it by the environment that you’re in.

Because of that, Legendary and Steven made the conscious decision that we’re going to do most of the action in day time. That, in itself, presents a lot of problems. Straight away, I sort of said, “Look, we’re going to shoot a plate for every single visual effects shot, even though I know we’re not going to use them all the time. There’s a lot of damage to the city, a lot of futuristic look to the city that needs to be augmented — there’ll be a tipping point on a VFX plate, where it’s deemed more economical to do it all CG rather than replace the buildings that exist in the plate.”

We set about looking at all the different locations where we needed to shoot. MegaTokyo, at the end of the film, that, in itself, was a design challenge. We couldn’t really shoot in Tokyo because of limitations of the street size. In order to get a Jaeger to run down the street, we needed a 70-foot wide boulevard. So, there was a conscious decision to find locations that we could augment into MegaTokyo.

One of the other aspects was the camera work. In Tokyo, there’s a limitation where helicopters are not allowed to fly below 500 feet in the city. A crane can go up to 100 feet but is limited in its movement. In order to do the physical moves for the plates, we used a lot of drones. There is a fantastic company in Australia called XM2, run by Stephen Oh, that provided drones for us. They had a mini Alexa on top of a drone, which would fill the gap between 50-feet and 500-feet. With 240-foot tall Jaegers and a 300-foot tall Kaiju, it all just all fit perfectly with the previs.

In previs, as you know, you can cheat speeds and cameras to move incredibly fast. It really grounded us having to try and shoot a physical plate in order to represent a previs. We found that certain shots were just impossible in terms of their physics. That really grounded us in making sure that the plates felt exactly like the shots we wanted and were photographed by a camera and not just left to be done completely in CG, which was really important to Dan Mindel.

AWN: With multiple groups doing previs, how was it all integrated? What was the goal of the previs? Was it geared more towards narrative development, techvis, or both?

PC: At the end of the day, previs companies hand scene files over to the visual effects company and we want to make use of them. If the director is spending time to finesse a particular camera in a particular way, he wants that move. It’s not like we’re going to take it into a visual effects house and then suddenly redesign it. Half the time, the director says, “No. Look, match the previs. I like the previs. I like the way it feels.” So, right off the bat, if I’d come on earlier, I would’ve set up the previs cameras with Halon, The Third Floor and Day for Nite, so that we were all using the same toolset.

Brad Alexander [Halon previs supervisor] Mark Nelson [previs supervisor] at The Third Floor and Andreas, were using their bespoke tools, motion-capture, all that sort of stuff. I would’ve set out rules and said, “Look, the average helicopter can move at a maximum speed of 100 miles per hour and it gives you this sort of feel. Let’s not betray the photographic quality between the live-action and what the CG camera’s going to do.” That was something I was very conscious about.

But in answering your question, at the preliminary stage, when I came on board, the previs was all about the narrative. Is the sequence cool enough? Have we got enough cool gags? Is this flowing? Do we track where all the Jaegers are in relation to the Kaiju? A lot of those answers were, “No, we don’t.” So, I immediately started storyboarding and working the whole thing out. I even setup a table…we bought toys from the first film – we got a Gipsy Danger, a Leatherback and various Kaiju from the first film – and used them as maquettes, moving them around, taking photographs and working out the sequences, so that geographically, we always understood where those robots were. That was very confusing in the previs I saw at first. You want audiences to relate to what they’re seeing. They want to know that if you cut from one shot to another, they can follow the story, rather than cutting to an amazing shot where they don’t know what’s happening.

We would always design the sequences around the geography as well as the cool gags that we put into the previs. I let DNeg run wild. I told Halon, The Third Floor, Day for Nite, “We want to come up with gags.” We want to see gags that haven’t been seen before. Invariably, they were always a regurg, something that we’ve seen before. But, we were very conscious of Transformers and Guillermo’s film, always trying to reinvent things and give a different perspective.

So, initially, there was a narrative focus [with the previs]. I would’ve locked the technical [techvis] down [earlier] so that it became more useful in post. This carried on even in postvis – DNeg and all of the companies did some [postvis], in order to help realize sequences [more quickly]. When editorial cut scenes, they realized that, “Actually, you know what, this doesn’t quite make sense. We need to redo that.” The whole of the third act, the end of the sequence, was a late addition to the film. The original Steven DeKnight script ended in a very different way. That went through its gestation period with Legendary and the writers and ended up being the sequence that you saw in the film.

AWN: It seems every movie that boasts giant robots, monsters and other creatures has some trouble with the issue of character weight and movement speed. How did you handle that challenge?

PC: That’s a great question. We were very conscious of those issues. The quick answer is there’s a trade-off between realistically representing a 2,000-ton Jaeger at 240 feet, moving in a certain way, to the sequence needing to be exciting and engaging for the audience. There was a compromise, right from the day one. Being a visual effects supervisor, you want to represent things physically the way they should be.

John Knoll [VFX supervisor on the first film] worked out that a Jaeger at that scale would move at one-seventh the speed of a normal human. Now, if we did a whole battle sequence at one-seventh speed, it would be a very slow and boring sequence. So, artistic license was taken, using editorial to help bridge the gap between the really boring bits and the really exciting parts of the shot. All of the previs was done long – editorial played an important role in making sure we chose the right amount of previs. Straight off, we were conscious that we needed to move at a certain pace. Sometimes it was cheated. If we didn’t respect that pace, all of our rigid body dynamics and effects simulations would also need to be cheated. We knew we were breaking up buildings, stomping things into the ground, splashing water and kicking up snow. Those [movements] obviously behave in a certain physical way, so we couldn’t wander too far from what a physically realistic robot would do in order to achieve that amount of damage.

There were a lot of trade-offs between all of the departments in order to get it right. But, once you started to feel the animation and the process of moving these creatures, you could look at a shot and go, “Hey, that’s moving way too quick…now, it’s moving way too slow…now it’s not working because although it looks real, it’s not dynamic enough. So, we need to either move the camera in order to counter it and make the move appear faster, or we need to put a longer lens on and cut out quicker on that shot.” There were a lot of compromises made in order to keep the action sequences as realistic as possible, but as fast moving as possible.

AWN: What was the experience like filming at the big Wanda studio up in Qingdao, China?

PC: Legendary Pictures is owned by Wanda, so there was a big call to use their facility in Qingdao. We shot in Sydney from late October through to the end of February [2017]. Then we went to Qingdao for four to six weeks from the beginning of March to pretty much the end of March, beginning of April. China is an evolving country and a powerful one in terms of deep pockets. But, there’s still a lot that they need to catch up on. Most of the key technicians that were brought into China were the original technicians [who worked on the first film]. So, there really wasn’t much risk in relying on a particular department that hadn’t been involved in the film before.

The production was smart and maximized the advantages of shooting in the Qingdao studio. The studio is brand new by the way — the stages were immaculate. Big stages…we had all the run of the facility. Labor is not a problem there. There were a lot of crews and people on set. But again, they needed time in order to perfect the look of the builds that were used in Sydney. That, I think, Stefan Dechant found a little frustrating. A lot of resources were flown in, in order to show the Chinese just exactly how to do things. For me, obviously being in the post side of things, I found the crews fantastic and their work great. And, in the end, the sets worked. It was a great experience to shoot in Qingdao.

AWN: Any new technology or approaches to handling the film’s massive amount of destruction?

PC: DNeg approached the environments as a kind of area, location-wise, because the continuity needed to flow in that same area from shot to shot. A lot of the continuity between shots was really laid out in the 3D world space, rather than what normally happens, where you take a much smaller segment, work within that, and then everything else becomes a digital matte painting or a 2 and 1/2D environment. A lot of it was much more 3D rendered because each robot and each fight had so much interaction around it that we needed to make sure the rendering didn’t break.

Portions were made into areas rather than the traditional way of bolting shots on one to the other in order to keep the continuity. It served its purpose well because if you look at the film, there was never a question of, “Hey, you know what, that building shouldn’t be there.” It should be there, because if you opened up the scene file, you could see the relationship between all those buildings and where that robot was. That efficiency, of knowing where everything was in 3D space, really helped define what the action sequences were. And, that was part of the pipeline.

Then obviously, every year, crowd and effects simulations, rigid body dynamics, skin sliding, textures, all that muscle work, all that creature IK [inverse kinematics], all of that gets updated to be more sophisticated. Clarisse, with ray tracing, gives a fantastic true-life simulation, based upon HDRIs taken from the live-action plates. Live-action plates now use these projections so there’s never a question about the lighting. Even lighting was tricky because we cheated on certain live-action characters. There’s a certain amount of cheating you can do with lighting. But, in the first film, with the night time environments, you could always put another spotlight or an ambient light here or there. But for us, we were grounded in live-action reference and reality that gave our CG artists a good head start.

AWN: Looking back, what were the most difficult and challenging parts of the production?

PC: First, the need to shoot plates was obviously limited by the footprint we needed to capture. For a Jaeger to run four steps, that’s a terrific amount of distance that we needed to block off, make safe, work out just exactly how wide things should be and where objects were. That alone, finding a location that would serve as the background plate, was a tremendous challenge in terms of being a logistical nightmare.

Second, Steven wanted to make Sydney, Siberia and MegaTokyo look very distinctive. There were different chapters in Gipsy Avenger’s life – think about the damage he carries from one battle to another as he degraded across the fights. This meant different locations and different looks. That was a challenge to design environments that satisfied the aesthetic Steven wanted for making these sequences very distinctive.

Then, third, one of the biggest problems was the amount of time we had to do a show this size. It’s safe to say, this was one of the biggest shows DNeg has done. They had to create a pipeline that efficiently made the models to the degree of detail needed, handled the animation and motion-capture aspects of the creatures and robots, plus the effects destruction, throughout all of these environments. This show ended up with almost 1600 shots, roughly. DNeg did around 1038. Atomic Fiction did 326. Ryan Urban at Turncoat Pictures did around 18 shots himself. In-house did about 216, so all in around 1600 shots. Creating that body of work in the short amount of time we had was a challenge. The end sequence, the third act, was really decided last minute — I think DNeg had eight weeks to realize that sequence.

Luckily, the pipeline for generating robots, animation and effects was in place to churn out shots quickly and efficiently. No time was wasted. Those three aspects were probably the most challenging on the film.

I love this business and that’s why I like talking about it. We like people to know what goes on behind closed doors because it makes people’s jobs easier if everybody understands what everybody does. I think visual effects is so complex and exciting. It’s just a great department to be working in. It’s fantastic.

![]() Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-at-Large of Animation World Network.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-at-Large of Animation World Network.

熱門頭條新聞

- The CES® 2025

- ENEMY INCOMING! BASE-BUILDER TOWER DEFENSE TITLE ‘BLOCK FORTRESS 2’ ANNOUNCED FOR STEAM

- Millions of Germans look forward to Christmas events in games

- Enter A New Era of Urban Open World RPG with ANANTA

- How will multimodal AI change the world?

- Moana 2

- AI in the Workplace

- Challenging Amazon: Walmart’s Vision for the Future of Subscription Streaming