By Jennifer Wolfe | Tuesday, November 6, 2018 at 11:05am

The story of a young boy shuffling between the homes of his recently divorced parents over the course of a year, the painterly short film Weekends blends surreal, dream-like moments with the domestic realities of a fragmented family in this hand-animated dialogue-free film set in 1980’s Toronto.

Weekends is written and directed by Canadian-born filmmaker Trevor Jimenez, who — working closely with production designer Chris Sasaki — oversaw a crew of 27 animators and artists to bring the project to life. Generating awards season buzz on the festival circuit, the 15-minute short film won both the Special Jury Prize and Audience Award at this year’s Annecy Festival, and topped two other Oscar-qualifying festivals, the Nashville Film Festival and the Warsaw Film Festival, in addition to a slew of other awards.

Weekends is written and directed by Canadian-born filmmaker Trevor Jimenez, who — working closely with production designer Chris Sasaki — oversaw a crew of 27 animators and artists to bring the project to life. Generating awards season buzz on the festival circuit, the 15-minute short film won both the Special Jury Prize and Audience Award at this year’s Annecy Festival, and topped two other Oscar-qualifying festivals, the Nashville Film Festival and the Warsaw Film Festival, in addition to a slew of other awards.

Jimenez has worked as a story artist for more than 10 years, most notably at Pixar, Cinderbiter, Disney Feature Animation, Illumination Entertainment and Blue Sky Studios. His student film Key Lime Pie screened at numerous international festivals including Annecy, Ottawa, AFI Fest, Zagreb, and Mike Judge’s “The Animation Show vol. 4,” and won the award for best animated short at AFI Dallas 2008. He is currently employed in the story department at Pixar, where he is working on the as-yet untitled forthcoming feature from Pete Docter, while also pursuing his own creative projects.

The film was produced as part of Pixar’s co-op program, which allows employees to use Pixar resources to produce independent films, but without full-fledged studio support. The program has already yielded short films such as Robert Kondo and Dice Tsutsumi’s The Dam Keeper (2014) and Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj’s Borrowed Time (2015), both of which received Oscar nominations.

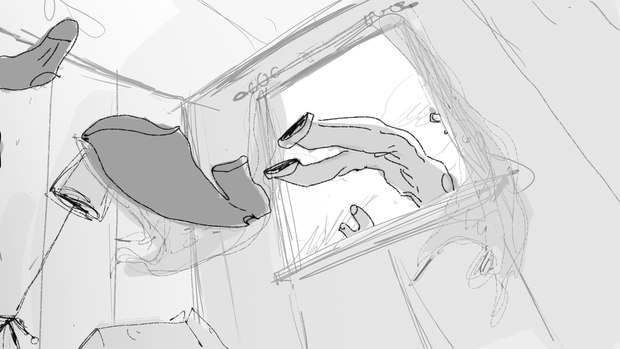

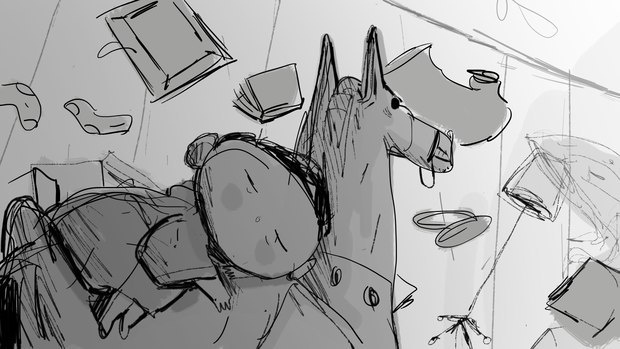

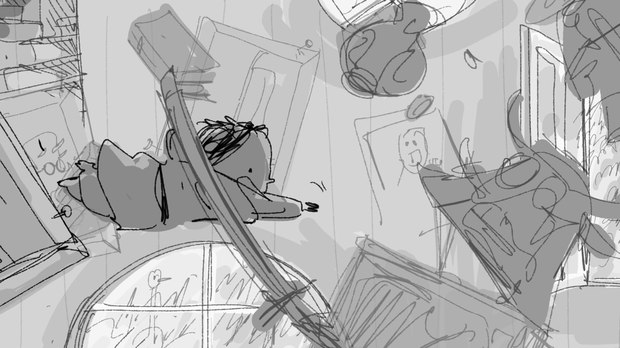

AWN met up with Jimenez during the ANIMATION IS FILM Festival, in October, where the director took a deep dive into what he says is one of his favorite sequences in the film. The roughly two-minute dream sequence is laden with drama, heightening the emotional stakes of the film. Set inside the family home, familiar objects take on a life of their own, swirling through the air and out the window. “The boy wakes up in the morning, like he normally would, and floats down the staircase, and then finds his parents in the kitchen, like he normally would, but they’re not actually there,” Jimenez recounts. “It’s just their clothes waving at him in this sort of slightly eerie, but happy, weird moment.”

The floating objects throughout the sequence were animated by Pixar story artist Madeline Sharafian, who also works on her own films in her spare time. “She’s a really amazing artist,” Jimenez effuses. “I wanted her to help out on the short, so she took on this whole sequence, painstakingly animating all these objects — the little t-shirts, socks and sweaters — floating out of the window.”

Inside his dream, the boy’s childhood home isn’t torn asunder, but it does transform into something else altogether as familiar objects float away. “Everything is sort of displaced and floating. It’s all familiar, which is comforting, but also unsettling in the way that nothing is grounded,” Jimenez says. “It starts off with the shot of a strange sky with a t-shirt flying, which is the first surreal image in the whole film. That’s when we break from reality, and from there we go in the kid’s room and everything’s floating out of it,” he describes.

“I like that kind of concept, it felt honest to me,” Jimenez adds. “One of the things that’s interesting about divorce is that there’s always this idea of possession, like shared possession with parents. All the objects everyone owns and how that gets divvied out between two people.”

Set to original music by Andrew Vernon the dream sequence is the only piece of original music composed for the film, Jimenez notes, explaining that the remainder of the soundtrack alternates piano music, which represents the mother, with the 1985 hit song by Dire Straits, “Money for Nothing,” to represent the dad. “I had always intended for the film to play out as a silent movie, with just sound effects that come from in-camera,” he says.

Early in pre-production, Jimenez knew he wanted sequences in the film that were surreal and helped express the emotional state of the boy. “There were a bunch of different dream concepts, and this is one of the earlier ideas I had,” he conveys. “The original inspiration for it was one of the first dreams I remember from being a small child, which was actually more of a nightmare. It was in my bedroom in the home my parents used to live in together before they got divorced. I had this dream that laundry floated into the room and suffocated me. But the light in the dream was very bright, with a lot of vivid imagery that helped me create the mood, and the visuals, I wanted in this dream to have.”

During the storyboarding stage, Jimenez initially planned for the dream sequence to employ a locked camera, but soon realized that a more fluid sense of movement was called for. “At first, I repeated this one shot with this kind of flat staging of the horse in the middle of the bedroom, which is how the dream started originally, with this repetition, but I found that, visually, I wanted to separate the dream from reality a little bit, so it’s the first time in the film there are any camera movements,” he relates. “Anything that feels more heightened has some camera movement in it, while most of the domestic shots are locked off.”

According to Jimenez, the added camera movement results in a more immersive and dream-like feeling. “The staircase shot also started as a locked-off shot, but then I added a little movement to it along with some parallax,” he adds. “Same with the reveal of the parents in the kitchen, that ended up being a tracking camera move into the kitchen. Boarding it, I knew I wanted to end on this image of parents that were just clothes waving at the kid, being very inviting.”

The dream sequence is suffused with a yellow light that Jimenez initially struggled to define. “The whole thing is sort of yellow and bright and strange, but it’s a very specific kind of yellow,” he details. “It’s a little sick, but not hospital-sick, if that makes any sense. It’s kind of nostalgic, faded.”

Finding that yellow ended up being one of the most difficult challenges Jimenez faced in making Weekends, but it ultimately helped define the overall look of the film. “It was really hard to find a color palette that matched the memory,” he says. “Then our production designer, Chris Sasaki, came on and he just nailed it right away.”

Working from paintings and an early color key of the yellow color Jimenez had completed, Sasaki “took the concept and made it more palatable and appealing,” Jimenez says. “He was able to develop a visual language to help communicate the mood we wanted using a simpler color palette, with more texture, that became the style we set for the entire film.”

![]()