Web Gaming Strikes Back

The resurgence of web gaming is fascinating, a trend referenced by legendary Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins’ speech at Slush and in the 2025 predictions of other industry luminaries.

The resurgence of web gaming is fascinating, a trend referenced by legendary Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins’ speech at Slush and in the 2025 predictions of other industry luminaries.

Casual, browser-based play was a large, growing market that pioneered much of the free-to-play design that now dominates on every platform, but it virtually disappeared with the rise of mobile in the early 2010s. After about a decade, what explains the web’s comeback as an exciting platform for gamers and game developers, and where does it go from here?

Why Web Gaming Died

In the web gaming era of the 2000s, firms like Miniclip developed their own arcade-style games and published them on their eponymous platforms while also allowing other websites to freely embed any game. Browser games became incredibly popular among school kids and were monetized entirely through ads.

Kongregate, meanwhile, operated as an open platform, adding thousands of new games per month and generating 80% of its revenue via IAPs at its peak through more midcore genres. EA purchased Pogo.com in 2001, and by 2003, had introduced a monthly subscription and in-app purchases to its catalog of card and casino games.

MMORPGs like Runescape and simulations like Neopets also attracted audiences of tens of millions of users, and Big Tech embraced the market, with platforms like Yahoo and Facebook becoming preeminent destinations for social games — the latter provided a launchpad for Zynga.

All of these games had one thing in common: They ran on Adobe’s Flash technology (with the exception of Runescape, which had a Java client) and were almost exclusively played on computers. The launch of the iPhone would eventually prove fatal to Flash. Steve Jobs penned an open letter railing against the technology and chose not to support Flash content on iOS. As consumers eagerly adopted smartphones, game developers followed. Once Apple permitted in-app purchases in free games in 2009, the mobile free-to-play era arrived: Players who once navigated Kongregate or Miniclip for Flash games started browsing the App Store for native mobile apps. Adobe eventually deprecated Flash in 2017, by which time mobile had long surpassed the web as the largest platform for free games.

From PC to Mobile

Today’s web gaming market has reinvented itself almost entirely. Flash has been replaced with HTML5 as the standard technology, and modern web platforms no longer fear losing players to mobile, positioning themselves as complements — and increasingly substitutes — for native mobile apps. Indeed, while the first generation of web games were played almost exclusively via desktop browsers, today’s titles are increasingly oriented toward mobile.

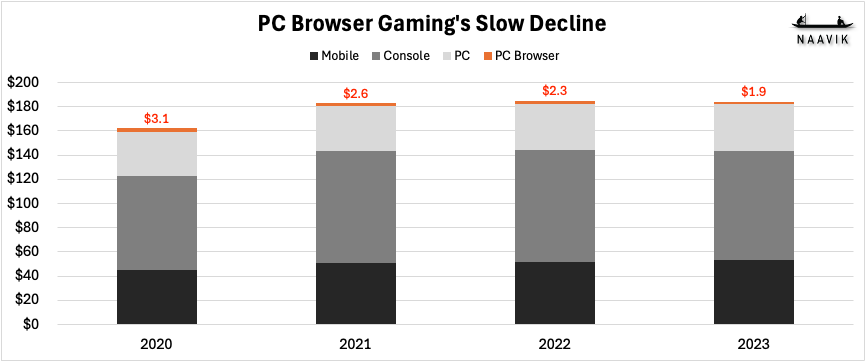

According to Newzoo’s annual reports, PC browser gaming has been in consistent decline. Note that Newzoo’s data does not include mobile advertising revenue.

According to data Naavik compiled from Similarweb, 28% of monthly unique visitors to the top browser gaming sites are on mobile. (However, this data excludes major platforms like Facebook and Yahoo.) Many of these sites, like Poki, have specifically courted the mobile audience and now require that all games on their platform must run on mobile.

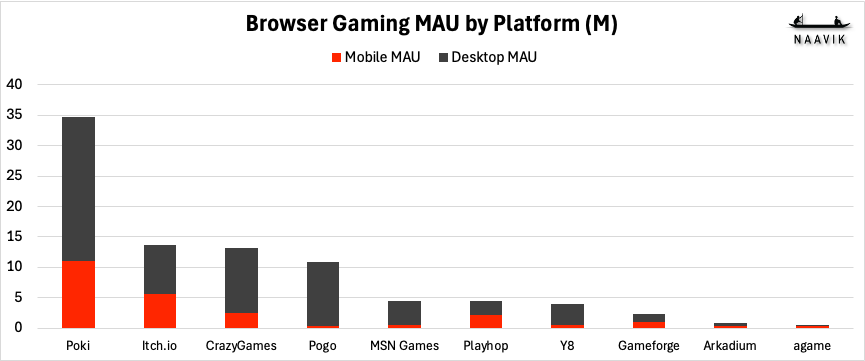

Source: http://similarweb.com/

Most users playing games via a web browser are still playing on a desktop computer, but there are now tens of millions of monthly visitors on mobile devices across the top sites | Source: Similarweb

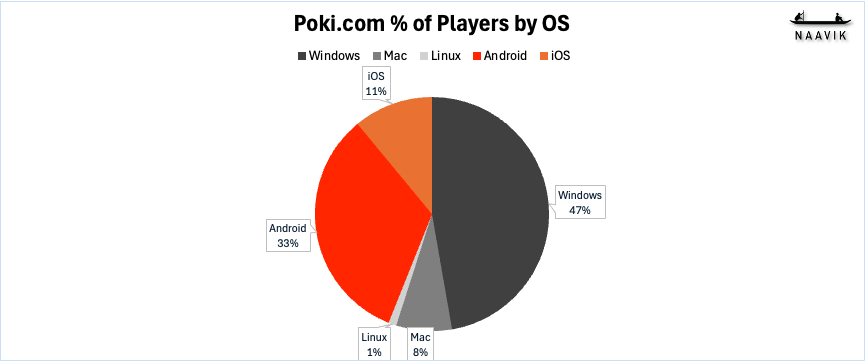

The percentage of MAU playing on mobile on the top 10 browser-gaming sites ranges from less than 4% on EA’s Pogo property to 52% on agame.com. Poki is far and away the largest of these sites, with 2.6 times the audience of its closest competitor CrazyGames (Poki claims to have 60M MAU on its site), and also has a higher proportion of users playing on mobile.

Source: https://developers.poki.com/guide/player-device-report

40% of players on leading web gaming portal Poki.com are on mobile devices, according to Poki itself (Similarweb estimates 32%). Note that unknown OS data is not included | Source: developers.poki.com

From Browsers to Embedded Games

In Asia, WeChat’s HTML5-based minigames have long been popular, but saw revenue climb 50% year-over-year in 2023 with the growth of IAPs and 3D graphics. Many Western apps, from Snap to Meta’s Messenger, and even TikTok, have tried over the years to develop a robust HTML5 gaming ecosystem in a bid to replicate Asian superapps, but without breakout success.

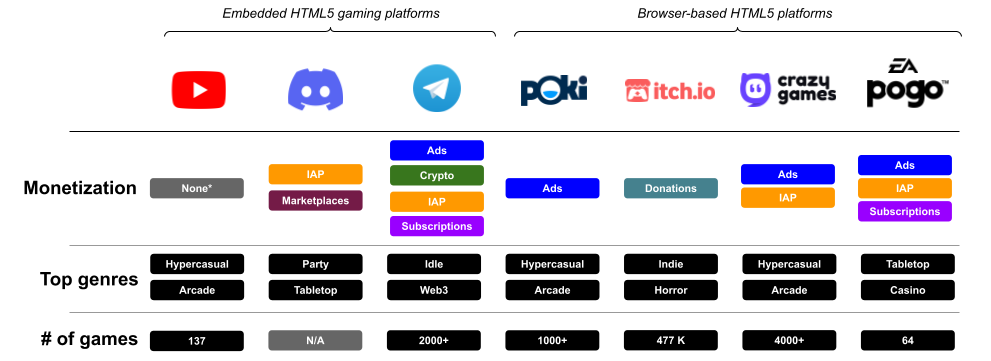

Lately, however, there has been another resurgence in HTML5 games embedded within existing apps. Telegram, YouTube, Discord, Jio/Swiggy, and even LinkedIn have launched gaming products, and leaders like Facebook Games and CrazyGames have moved toward IAPs. OEMs, telcos, and challenger browsers like Opera have also embraced HTML5 games. These games have a variety of business models, though many of the same genres and even many of the same games from browser portals, as well as mobile app stores, are available within each of these other apps.

Today’s top HTML5 gaming platforms offer a wide variety of business models and genres. Note that YouTube currently does not allow direct monetization of Playables

Discord and Telegram in particular are leaning into HTML5 games as premiere experiences on their platforms, with a variety of monetization options, support for social integrations, and advanced features like motion tracking and full-screen mode. Meanwhile, a16z portfolio company Lil Snack is pursuing partnerships, embedding its AI-powered daily minigames into properties like BuzzFeed and Amazon Games.

The Market Structure of Web Gaming

The flexible nature of web gaming also makes it difficult to define as a market, though a 2023 report from Google and Kantar estimated that HTML5 games generated $1.03B in 2021 and would grow to $3.09B by 2028.

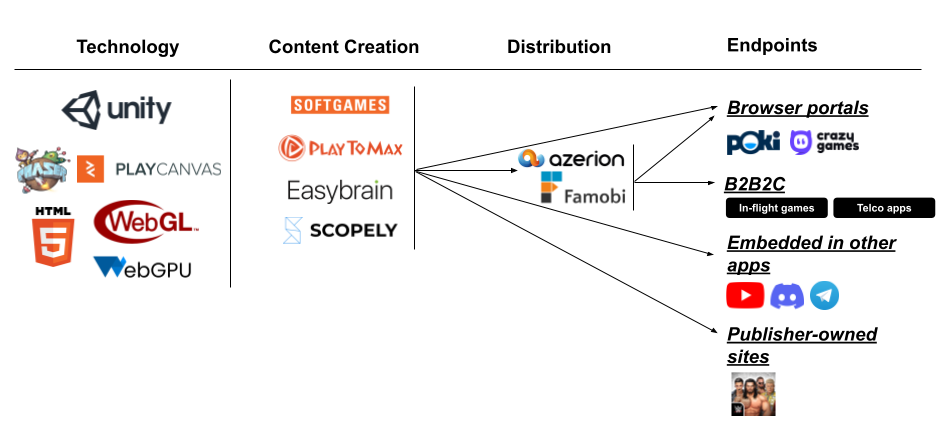

Where native mobile games are constrained to distribution via either Apple or Google, the web gaming landscape is highly fragmented, with key constituents being portals, developers, and distributors.

Portals are user-facing websites, like Poki, where game developers can upload their games after integrating the portal’s ad monetization SDK into the developer’s chosen ad placements. The portals share revenue with the developer — often small teams that focus exclusively on web games, though there are larger organizations (like FRVR or Softgames) that produce games for distribution via portals as their primary business, but also host games on their own websites.

This revenue share varies across different portals and isn’t always public, but some data points include Arkadium’s 75% revenue share and Gameflare’s 50% cut. While most portals are open platforms, they have a wide range of acceptance criteria — Poki is more selective than CrazyGames, for instance — and some, like Pogo, are closed services that either develop all games internally or acquire/license them from developers.

Due to this fragmented portal ecosystem, in many cases there’s a distribution layer between publishers and portals. Companies like Game Distribution (owned by Azerion) or Famobi aggregate thousands of games from hundreds of developers, and manage submission and distribution to game portals to maximize developer revenue. They also distribute through B2B channels to put instant games on in-flight entertainment, Wi-Fi login pages, and other B2B2C, out-of-home destinations.

Studios that create HTML5 gaming content can self-publish or choose to work with a distributor like Azerion or Famobi

What’s Driving the Resurgence of Web Gaming?

So, why exactly is web gaming back in the conversation after so long? There are three interrelated reasons.

Growth: User acquisition for web games, while not necessarily as precise as mobile UA (even post-IDFA), offers distinct opportunities for publishers. Web-to-web or app-to-web campaigns can leverage different signals than traditional mobile campaigns, and users can instantly jump into web gameplay from an ad, instead of needing to visit an app store first. Furthermore, once users are playing a web game client, they are more likely to download a native app (Easybrain’s solitaire.net offers a good example). Finally, many of the new instant game platforms like YouTube and Discord present games outside of the crowded advertising ecosystem, bringing large audiences to games without needing paid UA.

Monetization: Most typical web gaming portals have historically monetized through ads, or to a limited extent, B2B partnerships with telcos or transportation services. Support for IAPs, however, has taken significant strides recently, with a recent partnership between Xsolla and CrazyGames and Facebook Games offering IAPs on iOS. Mobile publishers have already embraced web shops to secure higher-margin transactions, and publishing an entire game client on the web is a natural next step. Scopely has led the way with web versions of WWE Champions, Star Trek: Fleet Command, and Stumble Guys.

Technology: Unity’s ever-growing support for web game publishing, as well as specialized engines like Phaser or PlayCanvas, make the web more accessible than ever for mobile developers. Underlying technology like WebGL continues to improve, as does the next-gen WebGPU. Meanwhile, adoption of devices that can run more complex 3D web games continues to expand both the addressable market for web games as well as the level of complexity afforded to developers. The web also supports faster iteration and experimentation than app stores allow, with the ability to ship instantly across operating systems and devices. Startups like Lil Snack and FRVR are leaning into this to rapidly ship AI-powered minigames at a rate unfeasible in native mobile apps.

Despite this momentum, there are still challenges for web gaming to overcome. Even as technology progresses, a performant HTML5 client is not possible for many games. Titles in noncasual genres in particular, which typically feature larger asset sizes, often cannot run a web client, and even casual titles require significant optimization. Midcore games pushing the boundaries of what the web can deliver often suffer from performance challenges — for example, Solitaire Home Story frequently crashes when I play it on Pogo or Facebook Games.

Source: https://www.pogo.com/

Pogo.com, created in 1995 and bought by EA in 2001, is one of the longest-lasting web game portals. It has transitioned from Flash to HTML5 | Source: Pogo

There are also business challenges. Web ad revenue, which delivers the vast majority of income on most browser-based portals, monetizes at a lower rate than mobile in-game ads due to a variety of factors, and IAPs and subscriptions are still rare (though growing). User retention also faces obstacles not found on mobile, due to the lack of OS-level notifications. Games, therefore, have fewer levers to entice a user back into a new session, yet must still compete for mindshare with games that are directly accessible from a device’s home screen, instead of through an intermediary layer like a browser.

The Web’s Next Steps

Where does HTML5 gaming go from here? One can look East to see a glimpse of the future. After a number of false starts, consumers, publishers, and technology have aligned to increasingly bring instant games into Western chat/video/social apps, which are starting to resemble the thriving minigame ecosystem on WeChat, Douyin, LINE, and other superapps. There are a few developing trends that will help solidify the web gaming renaissance.

First, increasing accessibility from the device OS will improve the viability of HTML5 titles beyond more transient genres. Telegram, for instance, has allowed users to save instant games to their device home screen, as they would any native app. Greater support for treating HTML5 games as Progressive Web Apps (PWA) — able to be “installed” onto a mobile or desktop OS via the web — will blur the lines between native and web to the benefit of web games’ retention, reengagement, and eventually monetization — though Apple in particular places limits on the capabilities of PWAs.

Second, greater IAP support from portals will entice mobile game developers to start supporting web SKUs. Genres like hybridcasual, match, merge, and casino are already popular on web platforms; monetize largely via IAP; and have begun to adopt web shops on mobile. Despite its market leadership in the browser space, Poki lags behind CrazyGames, Pogo, and others in supporting the trend of growing IAP monetization.

Finally, browser portals and app platforms need to begin orienting toward live services in the way app stores have. Greater prevalence and promotion of in-game events will further drive engagement, and platform-level live ops will become differentiators, similar to programs offered by Google and Apple. Pogo has long been a pioneer in this space with its Constellations and Badges gamification layer, and newcomer Lil Snack has been quick to make leaderboards and collections a core part of its offering.

Will 2025 be a breakout year for web gaming? The segment is well poised for growth, with investment from some of gaming and tech’s biggest players. As long as mobile native apps — the core substitute for web-based play — remain a red ocean with expensive growth and high platform taxes, expect web gaming to continue to grow.

Source: Carson Taylor, Naavik Contributor & Product Strategist at Samsung Electronics America/CrazyGames https://www.crazygames.com/

熱門頭條新聞

- Global Game Jam Partners with Games for Change for the First G4C University Student Challenge

- Qualisys: Streamlining Mocap Today, Exploring What’s Next

- XSOLLA AND UKIE ANNOUNCE PARTNERSHIP AT GDC 2025 TO EMPOWER GAME DEVELOPERS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THROUGHOUT EMEA

- “One of the Best Platformers of 2025” Ruffy and the Riverside Announces June 26th Release Date on PC & Consoles!

- Overwatch star Matilda Smedius to host NG25 Spring!

- SAG-AFTRA National Board Meets via Videoconference

- Double Dragon Gaiden: Rise of the Dragons Free DLC Coming Now

- Take a look back at Latvian animation spotlight at CARTOON MOVIE!