Travis Knight Takes Flight with ‘Bumblebee’ — Part 2

In the second part of AWN’s two-part interview, the director of Paramount’s new ‘Transformers’ sci-fi action adventure discusses the magic behind a compelling and emotional digital character performance.

Click here to read “Travis Knight Takes Flight with ‘Bumblebee’ — Part 1.”

With critics sarcastically, but sincerely noting that Paramount’s latest entry in their Transformersfranchise, Bumblebee, has an actual story with robots that feel like real characters, it’s understandable that director Travis Knight would express satisfaction and pride when talking about his film. After all, discussions regarding previous Transformer efforts don’t normally arouse passionate discourse on topics such as story cohesiveness or thespian excellence.

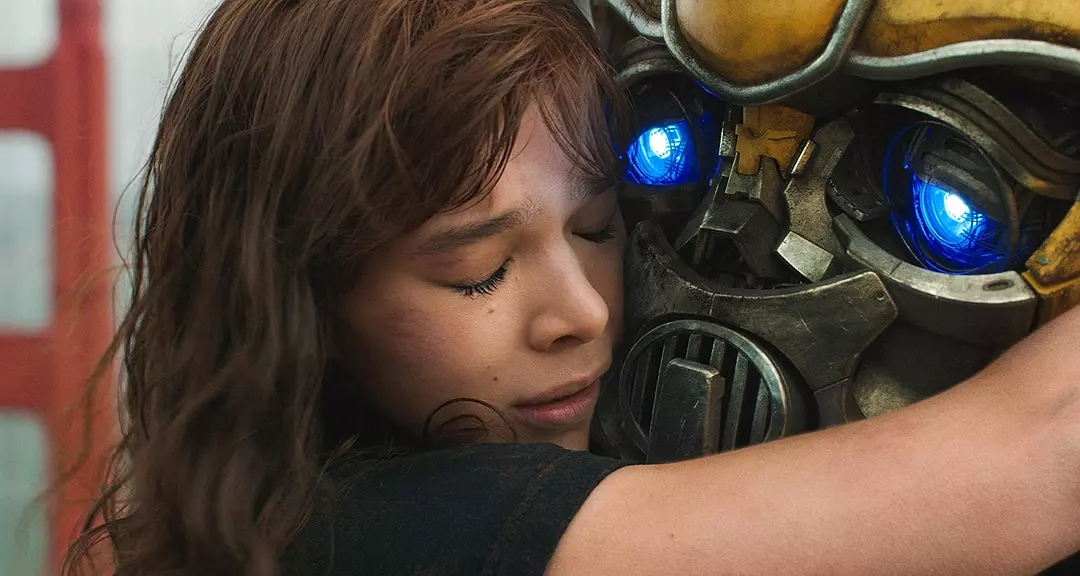

Bumblebee, however, in Knight’s capable hands, deftly engages audiences with not just a stellar and engaging performance by Hailee Steinfeld as the film’s protagonist, Charlie, but an emotionally compelling and believable performance by a completely digital robot. Suddenly, there’s a Transformers film where mere mention of acting or story no longer elicits exaggerated eyerolls.

In the second part of Germany-based journalist Johannes Wolters’s two-part interview, Knight discusses how he approached both the design and animation of Bumblebee, how Steinfeld’s performance was crucial not just for the film’s success but for providing animators cues on how to bring emotion to her digital companion, and how he used both music and stereoscopic 3D to help propel the story.

Johannes Wolters: What type of guidance did you give to evoke such an emotional performance with Bumblebee?

Travis Knight: As animators, we give life to something that has no life, that is just an idea! It’s the same whether you use drawings, puppets or CG models in a computer. We bring life to inanimate objects. And this means drawing from your own experiences, observations, thoughts and ideas as well as those of others to really make a believable character. I’d talk to the animators about clarity…“This is what Bumblebee is feeling in this moment! This is what he’s thinking in this moment!” Then, I’d let them work out the physicality…“You guys figure out how to bring that to life.” But when that didn’t go right, I’d say, “No, this is what I want!” Then I’d get up and act it out, looking like an idiot and feeling like a complete buffoon.

For me, Bumblebee and all the other robots, they’re not awesome special effects, they’re characters. The animators were the actors — you have to look through that prism otherwise you’re just going to get glossy spectacle, not an emotional performance. One of the things I am most proud of with this film is that Bumblebee is as much an actor as Hailee Steinfeld. They have a beautiful relationship. You believe he exists.

JW: And you had so little to work with…eyes and eyebrows…

TK: It’s interesting you mention that. Early on in the character design process, I talked with the designers about what kind of performance I wanted from Bumblebee. Their instincts were to add more details to the head, moving parts, different things that could move around. I looked at their first pass and said, “No, this is going in the wrong direction. You have to simplify. It’s not about adding details, but making the existing details mean something. Strip it down and clean it up, so the details that are there will be more powerful!” So, it really came down to a couple of brows, eyelids, and a little bit of muscle action. That was it. And making his antennas move. The expression is mostly in the eyes, which is where everyone is looking anyway. Studies have been done that show people focus right in on the eyes. So, we enlarged Bumblebee’s eyes, made his pupils bigger and more expressive. That’s the most expressive part of his body. And then you get his body language. But it really was about stripping down and simplifying the design. Making it clean, so the audience knew where to look.

JW: How challenging was the transition for you from animator and animation director to live-action director?

TK: Throughout my career, I’ve worn multiple hats. I see myself, to this day, first and foremost an animator. But over the course of my career, I have done many, many things. I worked in development. I have overseen different crews. I have produced films. I run a company. I have directed films. Having a foot in many different places makes you see things from different perspectives. I always felt that I had a great collaborative relationship with the directors I worked for. You have to! I mean, as a director, working in animation, you have to treat your animators as if they are actors. Because they are. They are bringing the physical performance. What you see on screen. They are bringing characters to life. And those are acting choices, the same way a live-action actor would make choices to evoke an emotion, a thought or a feeling to capture something honest. Animators just have to do that over a long period of time.

Pretty early on in my career, once I’d established an amount of trust with the director on a project, often times I’d be told, “Okay, this is what this scene is about. Now just go and do your thing!” And that is what an animator loves. You bring yourself to your work, infusing your own thoughts, ideas, personality and experiences to really make that scene come to life. That was the best. So, when I made the switch to director, I wanted to make sure that I gave the animators the tools they needed to bring their scene to life. And nothing else! That’s what is important…you let them do the magic! It’s no different with the actors. You don’t dictate to them. You want to give your collaborators just enough information so they can bring something of themselves to the performance.

There is an old saying that directing is 90% casting. There’s a lot of truth in that. You find really great people to work with and a lot of your job is done at that point, both in terms of the crew and the actors on the film. I was really blessed that I had really great crew, none of whom I’d worked with before, which was fairly terrifying for me going into a big film like this – I’d previously worked with the same people for the last 10-20 years. I didn’t know a single soul…not a single artistic collaborator whom I’d worked with before. I had to get to know people as we were making the film. That was pretty terrifying. But I lucked out in a lot of ways with how talented and capable the crew was. They really bought into what the film needed to be, what the film wanted to be. When you and your collaborators are all rowing in the same direction, and they all bring parts of their own experiences and talent, that to me is the beauty of film. All these different people, with different backgrounds, focusing on one goal…to bring life to something that doesn’t exist. And if it works, it’s magic! And I think this happened on our movie.

JW: You have to build up trust. Every voice has to be heard for the sake of the movie. There is so much input coming from all sides!

TK: That was something I was used to — questions, questions, questions, you get bombarded with questions! For every person, their department, their job, that’s the most important thing to them. You have to be mindful of that even when you are focusing on something that should take priority over, say, a costume choice which is happening two weeks down the road. You can’t forget people still have to prep for that. You have to be very, very mindful and sympathetic to what everyone needs.

I remember, with my director of photography, Enrique Chediak, he hadn’t really done something like this before and early on in the project, we talked about how I would see the robots — “He is over here and doing this.” Once, I was explaining to him what was happening, how the robot was behaving and moving. And Enrique said, “I do not see the robot!” And I said, “He is right there!” Then, there was really a big moment about half-way through the shoot, when we were setting something up and Enrique looked over to me and said, “Travis, I see the robot!”

JW: Did you bring a bit of your stop-motion production pipeline to this film?

TK: Breaking down the script, I thought, “OK, how do we visualize this? How do we make sure that the actors and crew know what my intent is, what is in my brain!” The only way I could think to do it was the way I always have done it – I’ll pour all this stuff out, all these emotional moments. This is what the characters are feeling, this is where Bumblebee is, this is the basic choreography, this is what he is doing. Those scenes were very CG heavy, animated sequences effectively. So, I made sure that we had animatics for all the key scenes. The first scene I boarded, one of the scenes I am most proud of in the movie, is where Charlie meets Bumblebee in the garage for the very first time. It’s a beautiful scene. I thought this is the one scene I’ll attack, because this is effectively the heart of the film. I wanted to make sure that we got it right. And I boarded the scene to death. No previs…just storyboards, because it was about the tone, making sure you felt the connection between these two characters. Other scenes, like the big battle scenes, we did some previsualization because there were so many things involved.

JW: Did Hailee Steinfeld’s performance help you animate Bumblebee?

TK: It was absolutely critical! Charlie, in Hailee Steinfeld´s hands, lifts your spirits and breaks your heart. With a different actor, the movie completely falls apart. She really carries the weight of the movie. She gave such a refined, subtle and nuanced performance acting against nothing. Not many actors can do that kind of thing. Part of acting is reacting. She had nothing to react against. It was all in her head. We had conversations about what the robots were doing, what she should do, how Bumblebee would react…so, we would talk about it. But, she had to get herself into a state where she could feel those authentic emotions with nothing there. And then she had to be the action hero, she had to be funny, she had to be smart, she had to be empathetic, she had to come up with this beautiful performance. And if it doesn’t work, the movie falls apart.

The other thing is, because Charlie and Bumblebee are effectively fun-house-mirror versions of each other – two sides of the same coin – their performances are linked completely So, when I sat with my animators, we talked about how Bumblebee’s acting choices had to reflect the same kind of nuance that Charlie was bringing. There is a sequence where they meet for the first time in the garage and it’s shot as if it’s in front of a mirror. That is who they are. They are kind of a reflection of each other. She is incredibly emotional in that scene and he has to be too! So, the animators used her as their cue, as their foundation. They studied what she did with her face. Hailee is such an incredible and intuitive actress, there was always something happening in her eyes. And the only things Bumblebee can really use to emote are his eyes. When you studied Hailee and what she was doing, you could imagine all these things happening inside her head. And that’s how we had to animate Bumblebee. He couldn’t just be this hunk of metal. He had to think and feel, and the foundation for animating that performance was Hailee Steinfeld. Without her it does not work.

JW: How difficult was it getting Dario Marianelli to score the movie?

TK: It wasn’t hard at all to get Dario onboard because I worked with him on two previous films. Music is such an important element in any film, but it performed many functions within our movie. There were certain feelings and ideas I wanted to evoke with the music. And for me, there is no one on Earth better [to do that] then Dario Marianelli. I gave him a call and said “Look, there is this film I’m doing!” He’d previously worked on my animated films, and he was very much interested in doing a movie like this, something he had really never done before. We sat down, talked about the touchstones, talked about the emotion, talked about the score as kind of an unholy union of John Williams blended with John Carpenter, smashing together with a lot of Dario in it. And I think he accomplished it. I am so proud of the score. It’s very different from the other Transformers films. But, I think it’s idiosyncratic and completely captures the tone and spirit of the era while bringing it into a new era! Dario is a fine artist and I would be thrilled to work with him again.

JW: If these robots could listen to music, what would they choose? Bach or Beethoven? Rammstein or Kraftwerk? How did you choose the music? Was it expensive to get the rights to the songs?

TK: Probably Kraftwerk. And yes, all this stuff is pretty expensive. But, we had a music budget, something I never had to play with before. I was like “Oh my god, we can actually afford to license some songs here?” On a fundamental level, this is a story of an adolescent coming of age, in terms of Charlie´s story. Thinking back to my own adolescence, music is often a tool we use to help us get through our lives. We have these weird inarticulate emotions that roar through our minds while we try to find a way to give them a voice. Music can do that. Hearing a song, you think, “Oh! They’re singing exactly what I am feeling.” There is a vibe to it — a heavy rock-song captures the anger and frustration I am feeling. You find a release in that kind of music. Music is so important in our lives and in this movie. Ultimately, it’s the way Charlie connects to the world and the way she gives Bumblebee his voice. He is able to speak through music, initially in a kind of ramshackle fashion where he is expressing a feeling or an idea, and eventually, where he is expressing more complex thoughts. So, in terms of theatrical choices, why those songs are in the movie is because I think they are awesome.

JW: You chose them?

TK: I did. So even though Charlie’s musical taste mirrors mine pretty much exactly, she is way cooler then I was. The bands she is into, like The Smiths, Elvis Costello, The Pretenders, those are bands that I loved too when I grew up, and they feel appropriate for her character. There is also some “poppier” stuff that we employed to give a feeling. The Steve Winwood song, “Higher Love,” that comes on when she is cleaning the vehicle version of Bumblebee for the first time, where we are tipping the hat about where this relationship is headed — this connection she has with this car, we’re leading the audience in this direction. It’s fun, upbeat and has meaning beyond the song itself. So, the pop songs were all chosen because I liked them and thought they were appropriate for the movie. The score was trickier to balance, because we had to evoke the era while not feeling dated. We had to blend the music harmoniously with all the different pop and rock songs. It was a tricky balance that Dario had to maintain and in the end he pulled it off beautifully.

JW: Did you have a certain female audience in mind as you developed this film? Or any specific audience?

TK: Interesting question. In the end, I didn’t really think about the final film and how people would respond. On some level, you have to trust your own instincts. When you make so many calls every single day, all those different choices, if you have to stop, step back and consider, “Well, how would this audience react,” well…I just tried to consider the kinds of stories that I love, that resonate with me and the people that I love. In terms of an audience, I thought about the people in my life and how they would react to my ideas. You have to keep it small. Once you start trying to generalize about millions of people out in the world, it becomes paralyzing. How can you know how they’re going to react?

Over years I found it kind of ironic. The more intimate you make something, the more universal it becomes. The more you dive deep into yourself, and really pull out some of those unpleasant things that are rolling around in the darkest corners of your mind, the more people see some truth. And they say, “Oh yes! I’ve experienced that! I thought that! That resonates with me!” While making Bumblebee, I just kept going deeper into things in my own life, my own experiences. That was my only guide because otherwise, there would have been no way. It was too big! There were too many things. To many different people. Too many layers. And in the end, it was about the people that I loved. The women in my life. That was kind of the driving force for that aspect of the story.

JW: How did you approach the stereoscopic aspects of the film?

TK: We had a lot of toys on the movie. We shot on Alexa cameras…we had an incredible Oculus system, a remarkable tool. What that thing can do! But, we also wanted the film to feel like it could have been shot in the 80s. We used a lot of technology around the high-tech stuff that was made in the 60s, 70s and 80s. We had lenses that were made in the 60s and 70s because that’s what a film made at that time would have been shot with. In my previous films, all our stereoscopic photography was native. We shot everything native. We would shoot the left eye and had those little micro-movers, which take the cameras slightly over to get the right eye. That got your perfect stereo image. Not practical on something like this. So, we used a post-conversion process. But I brought the same philosophy to stereo that I had on my LAIKA films.

A lot of times, when you watch a 3D film, it’s off-putting and actually hurts. It feels like you’re in an ophthalmologist’s office and your eyes are being pulled apart. It’s like, “Ahhh, my head hurts!” It destroys the experience for the audience! So, I wanted to make sure that the stereo on our film was employed with the same sensibility as the stereo I shot natively in the past. That was a bit of a gear shift for people on this film who had done this kind of work in the past. A lot of times, they’re thinking, “Flash! Bang! Oooh, lets goose the audience!” But, you have to do that in moderation. You can’t constantly throw things out at the audience. You can’t have weird things constantly penetrating the screen. That might work for a scene, or for a moment. But for an entire film, it’s fatiguing and takes the audience out of the movie. In the end it is about an emotional experience. And if what we are doing with lens choice, lighting and stereo doesn’t support the overall story and emotion, then it is not doing its job! So, that was the prism I looked through regarding stereo on the movie.

JW: There is a beautiful moment in the movie where Charlie comes into the living room and the family is sitting in the foreground while she is at the very other end of the room. The distance tells you everything about her family relationship. It works really well in stereoscopic 3D. This is one of the rare films which is better being seen in stereoscopic 3D.

TK: Thank you very much! That’s one of the great things about all these different tools we have to play with, like lens choice, light, color and music, to evoke a feeling or an emotion. And 3D, used the right way, can do that beautifully. Historically, as an industry, we’ve cannibalized that tool and made it worthless.

When we made Coraline, we realized that 3D was a cool tool we could use in service of story. We actually used it to get the audience into the emotional space of our main character. Sort of like in The Wizard of Oz, when Dorothy moves from her sepia tone world to the bright and beautiful of Oz, where everything is full of color and life. With Coraline, we tried to find the modern equivalent by using 3D to capture the world she lived in. It was compressed and claustrophobic — she was shut in. So, we kind of flattened the world. When she enters this new world and her life opens up, we suddenly have space, freedom, and oxygen. You can breathe. And the audience can sense that emotionally, even if they can’t quite figure out why it feels different using 3D to enhance that feeling.

JW: Is stereoscopic 3D that difficult to understand that filmmakers just choose not to use it like you do?

TK: I think they don’t understand it and don’t care. But, there are a lot of different things at play. 3D can be used beautifully to great emotional effect. Some filmmakers understand that, people like Ang Lee and James Cameron obviously. There are many others too. But at LAIKA, because we shot everything natively from the beginning, we tried to find an emotional reason, a storytelling reason, to use this tool and when we found that hook, we used it to tell our story more effectively.

熱門頭條新聞

- Take a look back at Latvian animation spotlight at CARTOON MOVIE!

- LBX Panel Submissions Now Open!

- How the “Flow” Reached the Oscars

- Sign up for Global Objects x Chaos Demo Day!

- Binge Now! Hear from 100+ Film & TV Industry Experts for Just $79

- S8UL is the only Indian org selected for Esports World Cup Foundation’s Club Partner Program 2025 among 40 top global teams

- Blood Strike 1st Anniversary

- INDIE3:Best Indie Games Summer Showcase is Back in 2025!