The Nature of Design, by Scott Lockard

Foreword

Design is not art. Design is not an art. Design is an act of translation and orchestration. Without criteria there is no design. Lochard’s fundamental components of design might be reductively called the four “C’s”

Client: co-creator of any design project

Criteria: the prerogatives and requirements of the client

Context: the larger circumstances within which criteria are applied.

Capability: the designer’s moral responsibility to address the criteria.

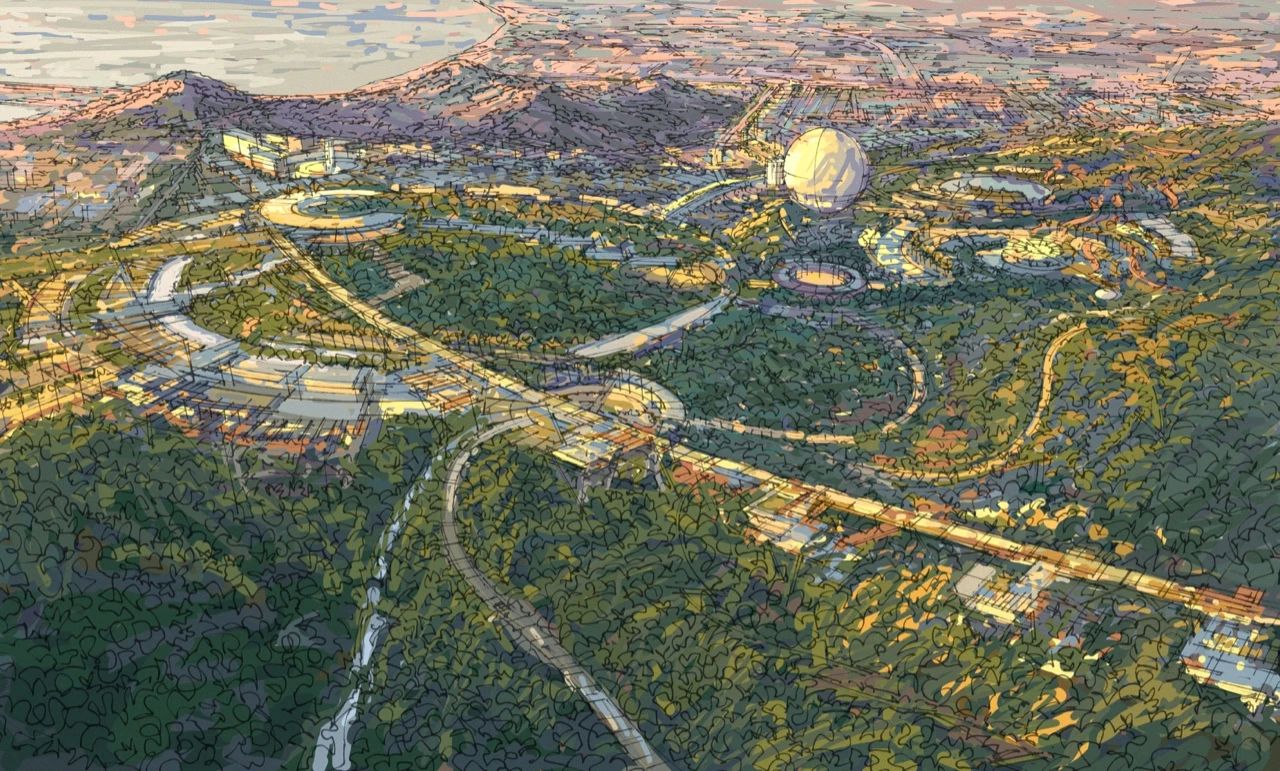

The visualization style is suggestive and interpretive rather than highly specific, occasionally reminding one of the finger painting.

Introduction: And who are you?

Whoever draws first, designs.

If you only do what is expected or requested, you will end up a manager.

It seems that proportionally fewer and fewer architects are ending up as designers.

Nearly all discourse on the subject of design falls into three categories:

Stylistic philosophies or design agenda of particular designers.

Technique, tools and process used while designing.

Criticisms or adorations of designers and their products.

The ability to design well is built both upon a thorough understanding of the design problem and the ability to propose, evaluate, adjust, propose, evaluate, adjust, propose, evaluate, and adjust. Any design must respond to criteria, and the inability to lucidly evaluate various proposals is the hallmark of incompetent, mediocre, egocentric, or just plain ignorant design. A designer must be able to efficiently and transparently evaluate his or her proposals against the criteria.

Point 1: Whenever we look even slightly more deeply into such a creation, we find instead an extremely large component of influence imitation and most importantly, client initiative.

Point 2: rather than some vague or idiosyncratic talent, designer is required to possess both broad experience and a specific virtuosity.

Point3: design is not art. It is not the private playground of the architect. Above all, design desponds to criteria. It originates with and exists to serve the client, the criteria are usually diverse and often in conflict.

A designer must be able to efficiently and transparently evaluate his or her proposals against the criteria. Simply put, transparency means that the method of evaluation doesn’t distort what is being evaluated.

Design is not art. It is not the private playground of the architect. Above all, design responds to criteria. Further, I would like to emphasize that sincerity is more important than style. One of the least important aspects of a project is the determination of architectural style

Design is a description of intent. Designers do not build buildings. The song the designer composes will be played by a large orchestra. After the design phase, the aim is not to lose too much in the translation. For this reason, a design usually benefits from some built in physical and intellectual maneuvering room, which might be called forgiveness.

The concept of forgiveness is intended to stand in contrast to the house of cards approach, the hoc is an aspiration to design perfection, whereby every decision is dependent on every other decision. In this approach, if one item or relationship is altered, the whole crazy thing might come crashing down.

Few buildings house such rigid and unchanging functions that they needn’t be modified or repurposed over the course of their lives, likewise, few functions are so rigid that they cannot be performed in a wide varieties of possible space or arrangements. Very many buildings are functionally little beyond bare square footage awaiting tenant improvements. To deny accommodation is to deny the nature of design.

Without criteria, there is no design. Design is not art. Design is not an art. Design reflects criteria and design responds to criteria. Design is not an act of creation, but an act of translation and orchestration. Art may be created for art’s sake, but a design is nothing if not viewed in terms of its specific criteria.

Establishing the prime criteria is not impossibly difficult as it originates with the client. The client is the creator of the design problem. Characterizing the designer as an artist may seem like a compliment, but in fact it belittles both designer’s responsibility and the client’s criteria- the very reason design exists.

Design is inherently unnatural, existing only through the purposeful actions of conscious beings. In order for these purposeful actions to be effective, they must be executed via a well-designed process, utilizing particular capabilities, and specific knowledge.

In its simplest form, the design process can be seen as having two parts: the problem and the solution. These can also be described as a prepare part (problem understanding) and a “propose, evaluate, and repeat part “(solution development)

The problem aspect is known, though not as clearly as it might be by architects as the program or as the design criteria. How do we actually come by these criteria? It is rare that a client is going to have the criteria completely spelled out, just waiting to be taken as face value.

Proper programming of a project is the first critical step in the design process. Many architects brush this effort off too lightly, accepting an agreed upon square footage tabulation and the zoning code as adequate. But many clients experience difficulty presenting criteria beyond space lists or pro forma. To recognize these issues and thoroughly define the program so as to neutralize experimental error is crucial to the entire balance of the design process.

There exist firms, and I suppose individuals, who define design only as a form imposing, visual styling, or even simply decorating effort applied to the planning and building system work of others. This we shall call little d design. While some little d design occurs in most any project, we will concern ourselves with big D design, which, strictly speaking, addresses a project’s criteria in its entirety.

Fundamental aspects of a design:

Vision: understanding and describing the client’s vision as well as possible will improve the chances of every other aspect of the design.

Concept: the concept is a comprehensive idea that can exist in the real world. If it is a good one, it accomplishes the goals of the vision. There are likely multiple good concepts that will fulfill a given vision.

Program: the program is the manual of project criteria, ideally it includes all the criteria, including everything from budgetary constraints to the goals of the vision. There is a bit of chicken and egg interaction between the concept and the program.

Design solution: a design that satisfies the program criteria in a specific physical form by arrangement of the site, space, buildings, systems, etc.

Image/style: the image or style of the design solution may take many forms.

Technical solution: we call this all the other criteria category, to include the building system, specific materials, engineering, building codes, and other quantifiable criteria.

One example:

Vision: capitalize on development opportunity made feasible by downtown revitalization incentives.

Concept: integrate housing, retail, and public space into one catalyst project.

Program: 200 midmarket residential units, 50,000 sq ft retail, 15% of site as public amenity.

Design solution: town center with small park and plaza, retail and town home layer with parking behind, service between, and condos above with podium level amenities.

Image/ style: contemporary, casual, appropriate to target demographic.

Technical solution: post tensioned concrete frame, EIFS on metal stud exterior, distributed mechanical system, market-standard finishes, etc.

About half of any full service architectural commission is not design, but construction documents and supervision. The client is the author/creator and the designer/architect is there to help pull a big piece of it off. As important as design is, it is only one part of any project. A designer’s expertise ability, and purview to help only extend so far.

It is really until the 19th century, the idea that an artist might create something from their own point of view was almost unheard of. The same situation applied to music. This is primarily because someone else was paying for it. Nowadays the artist or musical artist does things speculatively, there are still many commissioned things, but they are no longer regarded as art. They are now known as illustrations and soundtracks.

I would suggest that one way to define art is to view it as natural, possibly just what one individual wants. Beauty need only be in the eye of the beholder. This contrasts with design, which is unnatural- what a group of people wants. Design thus implies inherent conflicts, and is therefore never ideal. With a design, some may like it, some may not. It may be more or less successful, and its value may vary from person to person. But with something natural, there is no judgement. It simply exists. While we may not like some natural things like hurricanes, we are not free to question their validity or to not believe in them. With art, if just one person wants it, likes it, or creates it, that is enough. We can like or dislike it, but we can’t disprove the validity of its creator’s explanation that it was something they meant and wanted to create. In practice then, the product of one mind might as well be the product of no mind, a natural thing simply something like that is. Art is such a thing.

Architecture itself is now comprised of many separate specialties of which design is only a small component. In the case of most design professions, the great majority of individuals engaged therein are not doing design. Firms employ architects who functions as marketers, managers,….

Most practicing architects are not designers

The case should be made that, rather than any isolated act of creation, it is this complex orchestration that best defines design. Thus I would propose that rather than originality or creation, the measure of design is in the elegance and inventiveness of an orchestration that satisfies the criteria.

Step One: Prepare. Establish the Program. Programming Defined

In the realm of architectural design, programming has a particular definition that we will honor. The program is the criteria, and programming is the establishment of this criteria.

There exist at least two schools of thought on the subject of programming. The more analytical problem seekers believe that the criteria can and must be established separately from and preceding design. This approach is founded on the belief that proposing solutions before the problem is defined will alter or contaminate judgements regarding the true criteria. A leading proponent of this approach is William Pena, and his Problem Seeking is the classic guide to rigorous programming.

The much larger danger, however, is that the client will be led astray from their true needs by the designer’s doodling. The designer is often the biggest sucker for this problem- anxious to get to the fun part.

It is only reasonable that there is a bit of chicken and egg interaction between the concept and the program. The program tells us what will fulfill the vision, but not how, thus as particular concepts are developed, specific program elements may evolve. Programs may use test concepts as a ways of trying down the program, and illustrate programmatic concepts with analogous precedent projects. To some degree, the program is only truly finalized concurrently with the design, when all the criteria have finally morphed into a specific solution.

So many programs do change substantially during the design process, and keeping track of why and how they have is the proper procedure for program modification.

Big projects require a separate programmer and programming effort due to their complexity, but also as critical space and dollar budgeting tools. There are firms for example, whose entire business is healthcare facilities programming- they do no design.

On the other hand, in the case of many projects the programmer is the designer. An office building or retail center, whose users are inherently TBD, requires relatively light programming…

Notice that a complete program contains a great number of vision, conceptual, experiential, and stylistic criteria. While not strictly quantifiable, these criteria are every bit as important as the gross square footage. Many designers are trained to bristle at having to accommodate conceptual or stylistic criteria, but these constraints are aids to success, not obstacles.

Making up criteria is art. Making up, rather than deriving, criteria invariably indicates that someone skipped or didn’t value responsible programming. It is no mistake that many brand name, whatever I say goes designers make up or impose their own criteria… It is the lazy or incompetent designer who wants to ignore what might be difficult or compromising. Design is, by definition, a compromise.

Step 2a: Propose a solution. Big rocks.

Some rocks are clearly bigger than others. The program is a big one, and was of course arrived at through a serious rock sorting effort of its own. While the size and precise nature of the rocks vary from project to project, when it comes to the propose/evaluate part of the process, the biggest rocks are usually: the gross program, applicable regulations, the budget, and any idiosyncrasies of the site related to things like orientation, access, topography, or views. Medium rocks usually include various building and construction system choices, planning arrangements, and big stylistic or iconic gestures. Small rocks might include things like colors, materials, and fixtures.

Good programming should identify and grade its own rocks, but because programming is essentially a body of assumptions, if and when conditions change, some of these assumptions may become invalid. It is not usual to forget the reasoning behind some programming decisions, but if the design criteria are to be kept up to date, the validity of the program must be continually re-affirmed. A rock’s size can change in response to other changes.

Step 2b: Evaluating the proposal. Evaluating a design

Architecture is a language. The users’ ability to properly understand its message is an important measure of its success.

Even a finished design is not the actual thing, but rather a description of certain physical aspects of the thing. It is not the creation of something but rather the skillful orchestration of the responses to multiple criteria that define good design.

In the architect’s case, he or she can be the composer, but can’t effectively be the performer, as this requires too many people. Most project requires an orchestra. The design here is not the performance, but rather the scoring and orchestration.

Various buildings need accommodations (forgiveness if you will) in various degree.

The official critical/ academic world takes great care to divide designers into philosophical and stylistic cams. There is tremendous focus on identifying the latest leading practitioners and their creations. I would postulate that the most informative and valid categorization of designers and their behavior is by their aspirations.

Originally, genius was defined as each person’s guardian spirit or nature. Each of us had a genius to the extent that there were good geniuses and bad geniuses and run of the mill geniuses. Being a genius didn’t mean you were special, just that you were a human. Over time, the in use definition of genius has evolved away from something spiritual toward something seen as an inborn human characteristic, and at this late date in history, we regard genius as something that bears mention only in cases of exceptional intellect, influence, or capability…. Originality is one of the holy grails of modern definition art, and as you know, many designers enjoy behaving like artists.

Some of this reverence for creativity was no doubt due to the unprecedented inventiveness of the entire post industrial revolution era. While invention in those terms differs significantly from artistic inventiveness, inventive people in all walks of life found themselves enjoying new level of respect and celebrity. This somewhat abrupt shift in attitudes regarding originality, which culminated in official Modernism, created a break in the developmental continuum of art and design.

We must acknowledge the fact that all the really big innovations in design occur through engineering or the need to accommodate a new technology or function, and not through some designer’s vision.

What is the nature of genius? It is possible that the facet of originality we see in genius is simply an expression of the uniqueness of the individual. The nature of genius may be as varied as the unique nature of each of us. To return to the original definition, that uniqueness is our genius.

Championing uniqueness or originality presents some problems in that there is nothing new under the sun. Everyone has been influenced by everything they have ever seen or heard.

In an attempt to more precisely describe the role of influences, I suggest looking at one axis of the creative process, as a continuum, having at one extreme the verbatim re-creation of some precedent and, on the other, a totally original, unprecedented creation. Neither extreme is actually attainable, due to the existence of influence. On the one end, exact re-creation cannot occur in a pure sense because the process that will generate it and the context in which it will exist will be different. On the other end, nothing van be conceived in a vacuum. Creations must be assembled substantially from bits and pieces of existing creations. It is the assembly (orchestration) that will inevitably allow the most originality, but again success is measured by the criteria, not by the volume of originality.

One other aspect of dealing with influences is what I have been calling inventiveness. This quality does not run directly along the re-creation/ creation axis described above, but rather is measured according to the degree in which precedents exist, but are applied in a particularly effective manner, arguably at their most interesting when several disparate aspects are resolved by a single action. Inventiveness has an optional relationship to elegance or economy of means in terms of addressing criteria in the most efficient fashion. In science, the more elegant theory has often been shown to be superior to the more complex. In design, this is not necessarily the case, as the criteria are not necessarily a universal truth.

Allow me to suggest one idea for the proper use of genius, particularly as it is expressed in non- artistic realms. How is genius expressed in the scientific world? Practical geniuses like Newton, Einstein, or Feynman didn’t create new realities. Their concern was the understanding of a pre-existed reality, not the personal creation of an individual, idiosyncratic universe.

The genius of scientists, explores, and inventors result in the increased understanding of natural phenomena, but the genius itself is in the thought process, the methods of investigation, and elegance of experimentation. Einstein was solving for natural phenomena, not creating them.

How does this relate to us? Let’s consider for a moment that the client’s criteria are natural phenomena. The client is the artist here, after all. As I have postulated, the product of one mind might as well be the product of no mind, a natural thing. The program is not our creation, but rather a phenomenon that we must understand. Thus the proper application of the designer’s genius is to the process and not directly to the product. Taking this approach allows the criteria to be met and the genius to be used only for good- that is in the service of the client- and never against nature.

While an ism might describe a designer’s personal philosophy or theory, in terms of their actual process and practice, the important distinctions run along the aspiration-to-genius line.

Type One designers: Big Agenda Designers (BAD).

1a: The visionary Genius. Howard Roark: A house of Cards vs. Accommodation.

The genius makes each decision and knows which decisions are the perfect ones, and so in the end has a perfect design. The only way to ensure a perfect design is to make all the decisions oneself. But, deciding everything oneself is art. These architects are not asking for any forgiveness. They endeavor to limit or eliminate compromise in their vision of design, their art.

1b: the Name Brand Designer. This is What I Do, Developing a Product Line.

Argue if you must, but know that usually, though it is likely represented as philosophically deeper, this vision is essentially a personal approach to aesthetics, geometry and / or materials and their applications. This is one definition and one function of a style: to provide adaptable treatments and ready- made solutions for the various architectural conditions that arise in a project. It may include particular approaches or even styles of planning, but for the brand name designer, the distinctive qualities need to be most evident in a design’s aesthetics and not necessarily in the quality of its response to the criteria.

Often in practice, planning, context response, building systems etc. get the short shrift, and style gets all the attention. Of course in many projects, the planning is not particularly challenging, and even when it is, the designer’s skill can be harder to discern. There is a tendency to take the planning in a completed project at face value as it is more difficult to understand the constraints and criteria that shaped it. The quality of the planning often only becomes evident when it is extra-bad, as when some particularly awkward path of travel is imposed or a great view is ignored.

In contrast, style is the shiny object that can draw anyone’s attention and easily rendered opinion. It is especially unfortunate when poor planning is the result of the dominance of style over the functional criteria. It is incompetence or even contempt for the criteria that allows such a situation to occur. Fortunately, people are reasonably flexible, and often easily adapt to less than ideal facilities. They often don’t even recognize that things could have been better.

There are more aggressive/ evangelical brand name architects and more passive types. The more aggressive might state that regardless of what you want, you should do it my way. The more passive approach is, this is what I do, if you like it, great, I will do your project that way too. The problem in either case is that the client’s problem is being solved from a limited set of possible answers. I guess one could argue that this is always the case to some degree, because no one’s capabilities are infinite.

A forgiving interpretation might consider that brand names are taking the approach that this is what I do, and that I am only seeking clients who see and vale the world in the same way. A probably excessively forgiving interpretation would hear them saying, I don’t want to do something I can’t accomplish well.

Two (but only two) potentially negative tendencies occur in the case of the name brand designer. The first is that the designer’s personal preferences are often applied to each decision, apropos or not. Some effort may go into customizing, and hopefully the range of available products will offer up a workable solution. The second tendency or corollary is for clients and critics to expect similar solutions for all projects, regardless of context or criteria. This happens with musicians who try a new genre or, as with Woody Allen, when the aliens wanted him to go back to his earlier, funnier style. In case like this, client who ignore their own criteria are trading some amount of program-responsiveness for art.

Type 1c: The Theorist. Schools & Credos: This is What I Would Do.

Theorists, critics, and other kibitzers have the luxury of telling everyone how things should be, without the difficult tactical problem of accomplishing it. This allows for more critical and free thinking, unconstrained by budgets, client criteria, codes etc., which if done well, can be of benefit to the practitioner. Unfortunately, as largely undisciplined and untested personal opinion, it can also allows for serious hoodwinking of unsuspecting students, clients, other critics, and the general public.

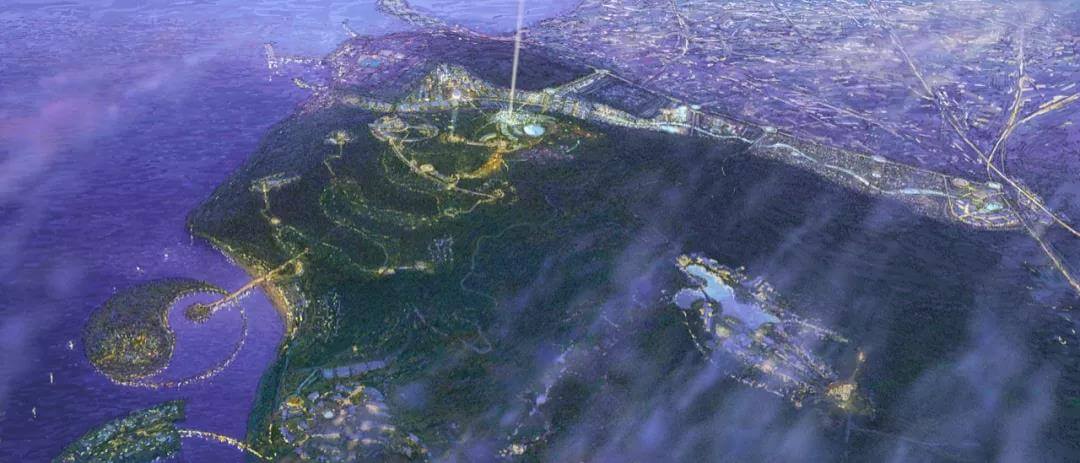

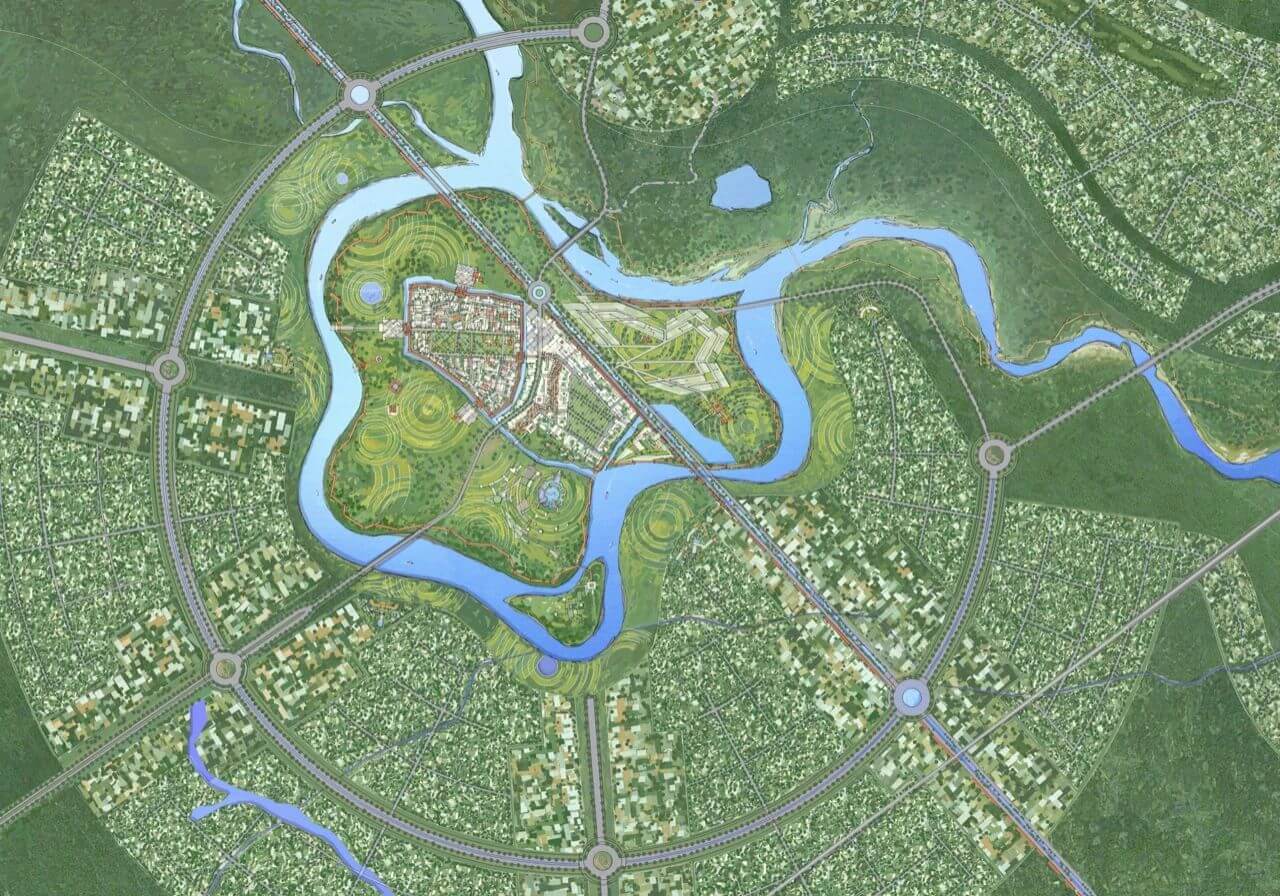

There are and have been more than a few great architectural thinkers. However, the inefficiency and inaccuracy of architectural experimentation means that most conclusions are more than a bit subjective. Much theorizing takes place in essentially no conclusive realms like planning, as in urban planning and master planning. This is indeed an area in serious need of good thinking. Reginal and urban planning clearly have greater impact on everyone than any single building might, yet the client, and thus the criteria, are more difficult to define.

It would be significantly more helpful if the architectural theorists acted like real theorists- as practical, criteria testing resources for both designers and clients- rather than being just one notch more arcane than the designers themselves.

Mr. Pain

I worked on several projects with a design who (maybe) should have been a planner. No matter what existing conditions, constraints or criteria where placed before him, he spent the bulk of his effort trying to change them. This he would do to the point that, after he finally had to capitulate 90% of the original criteria, there was scant time to develop a decent design. It seemed he thought it was his responsibility to architecture to challenge every given, every assumption and every request of the client. That without unnecessary pain, there could be no gain. He seemed to be more interested in broader planning issues, and less interested and subsequently less capable in actual architectural design. But it is also possible that the existing conditions didn’t always accommodate his agenda. In either case, his original sin was ignoring the criteria.

The Rug Guy

The corollary to this man is a fellow I have worked with who loves to draw designs (ie 2 dimensional patterns) all over the elevations studies his underlings bring to him. He has little or no interest in the functions behind these walls, the materials of which they are made, their structure or their relationship to the people who will one day gaze upon or out of them. The designer should be employed making rugs or stained glass or perhaps upholstery. He is just entertaining himself, not take the criteria seriously. He doesn’t know what design is.

Of course, most design, appropriately, occurs in the middle, i.e. somewhere between urban planning and the furnishing, where most of the client’s crucial problems lie. The planner and the rug guy, particularly if in positions of authority, tend to horn in on and foul up the real work with their peripheral interests.

Type Two Designers: Small Agenda Designers (SAD)

Type 2a: The Program Regurgitator. Functional Planner: Lowest-common-denominator criteria solver.

Type 2b: The Revivalist. Going at it in some old style.

Another tendency in revivalism is what is called theming. In the simplest terms, this is only a matter of going too far, too insincerely, superficially, or for the wrong reasons. Theming is not categorically different from any particular ism or approach to style.

Type 2c: The contemporary Elf. Going at it in the current style.

This designer is possibly the most common of all architects. This is the guy who is working in the current style…. The fact that they are responding to the criteria can benefit a client much more than a more imaginative, but misguided, effort.

Type 3 Designers

This category of designer might be called agenda-less designers. There are various reasons designers may forgo a design agenda, but it is not just because they are unprincipled cads. Our Type 3 design has great design capabilities, and the distinctions are in how these powers are used…. Type 3 designers are not necessarily the saviors of the profession. A Type 3 designer is sometimes a double edged sword.

Type 3a: The Virtuoso. Stanley Adshead. Hugh Ferriss, Syd Mead.

3a:Every designer has some skills. Some might call them talents, which is a bit more loaded term. To some, talent implies something that may be innate, and therefore possibly unachievable by most. So I suggest we stick with skill, and the implication that skills are generally learnable, if sometimes requiring great time and effort. It might be reasonable to call the aggregate of these design skill. Design skill would therefore be defined as a collection of skills, each in its own measure. There are analytical skills, compositional skills, three dimensional problem solving skills, communication skills, etc.

Continuing to ignore the chimera of talent, I might be willing to believe that skill could as easily be called technique, which is even more clearly in the learnable category. In a broad sense, every conscious thing, even thinking, is a technique. More commonly, technique is known as a method or procedure, perhaps even a very difficult and complex one, but one which can be measured and described. Virtuosity is simply defined as having fabulous technique. The term is often used in describing a feat violinist or other musician, referring specifically to their ability to play their instrument.

Virtuosity can even be applied sarcastically or insincerely, Satire is most convincingly delivered by a virtuoso.

The main criticism of the virtuosos by Type 1 and 2 is that this person is too good at one aspect of design to be good at others. Versatility and responsiveness- the very things they often stink at- can be seen as a lack of purpose. Type 3 designers must have no belief, no convictions, or credo, unlike the BAD guys. The virtuoso’s speed and fluency is even sometimes looked upon as some sort of trick.

The virtuoso might be viewed as the character actor who takes every part while the Type 1 designers are holding out for just the right script…. The virtuoso doesn’t view a single project as his or her one big chance. They like the process as much as or possibly more than the product.

Still, some artsy designers would say virtuosos are not being true to themselves (whether or not they are being true to the client). But perhaps Type 3 more clearly sees the multiple great solutions that exist.

A real virtuoso is not just a specialist. Great technique is the result of a comprehensive understanding of the entire discipline…. Even though they can do a million little things that made you say wow, under performance conditions they were actually less successful than many of the low-skilled guitarists attending the workshop. Were they really virtuosos or were they just deep but narrow, with no musical soul? Did they spend all their time working on weird scales and fingering technique rather than composition, improvisation, or crowd pleasing showmanship? So maybe virtuosity is not always good. No, the un-fun guitarists were not virtuosos but specialists, while their leader was a well- developed generalist.

Type 3b: The Hack

Rather than those trumped up charges of being too versatile, hackism can be the Achilles heel of the Type 3 no agenda designer. The defining quality of the hack is insincerity, and we have proposed that sincerity is extremely important. This is because sincerity is defined most simply as taking things seriously. The hack is at least somewhat perceptive, has some capabilities, but is too uninspired, cynical, or chicken to take the job seriously. He or she may even be a fallen virtuoso.

One should remain aware and wary of the following situations:

- Hit song: some of the hack’s problems parallel those of the Type 1 designer. The hit song or one style musician or architect may not be perpetuating the problem (non-versatility) solely on their own. The fans, producers, and record company are asking for certain things. Designers can find themselves typecast, and it can require particular effort to make clear to a client what criteria compromising choices are being made when design is simply taken out of the drawer.

- The new: it takes time and effort to understand existing things, practices, and ideas. It is so much easier to be free, to make it up as one goes along (very artsy). This is why it is difficult to do good responsive buildings. One has to first understand what exists. That takes time, and humility.

- Mythical justification: “I know they said square, but what I think they mean is just polygonal”.

- Bad hearing:

- Comfort: In Type 2 designers, creeping hackism often occurs along the path of least resistance. It is one’s obligation at such time to remind the client of the original criteria so that any modification of it is a conscious act.

- Systems: other potential hacks are specialists, in that some of the efficiency of their operations is in knowing the shortest path to the answer. While this may be appropriate for many problems, most design problems have some measure of uniqueness as well as some appropriate opportunity for innovation. Of course one should not design a building with a novice. The good generalist (designer) incorporates the knowledge of specialists while keeping the broader criteria in view as he or she orchestrates the solution. Regardless of the special requirements of a project, the majority of conditions requiring resolution are architectural in the general sense.

Being a hack is unprofessional- and unsatisfying. Where is the invention, the delight, the earnest thought, effort, and application of your skills in the service of the client? Not taking these intrinsic obligations seriously is hackism. Thus a strong case can be made that Type 3 isn’t the only, or even the worst hack. Working inflexibly the style of the day (Type 2) or nothing but your style (Type 1) is also hackism. The bottom line is that providing a less than sincere concern for clients, their criteria, and the development of means with which to serve them defines one as a hack.

Let us not forget that much of the heroism and genius we witness in the world of design begins with our clients, and that any opportunities we may have to practice our own genius are bestowed by them. We must also recognize that most if not all of the physical means (i.e. technology, materials, and systems) with which we can express that genius were created or discovered by some inventors, engineer, entrepreneur, or long dead builder. There is no shortage of genius or insightful criticism in the world, but its proper recognition has been eclipsed, misappropriated, and inflated by the promoters. One influence of this heroizing effort is a serious de-valuing of fundamental skills in the ordinary designers.

Artlessness

Can we define a single, paramount quality we seek as designers? What is our quest? I have come to the conclusion and will state with some certainty that the quality we seek is artlessness- free from guile, art, craft, or stratagem; simple, sincere, unaffected; undesigning. I would take free from craft to mean not sneaky, and undesigning to mean without an agenda, i.e. not schemingly, but not literally without design.

Another term to clarify here is authenticity. Thus us what many artists seek, saying with some gravity, find your authentic voice. This is an art attitude akin to be true to yourself. Architecture and design are inherently not authentic in this sense. Issues of style, image, encouraging certain behaviors, circulation patterns, and methods of functioning are manipulative (hopefully benevolently so). Designing is not a matter of being true to oneself, but rather of being true to others.

Insincere designers are not necessarily artful, but may be jaded, unimaginative, or incompetent. At some level, they have given up sincerity, perhaps worn down by bureaucracy, maybe value engineered one too many times, or sold out by a manager, but in any case, they have thrown in the towel to the demands and constraints of design. Maybe they lack the process needed to orchestrate good design. Maybe they lacked the virtuosity, responsiveness and energy required to develop, adapt, and follow through every time. Maybe they didn’t educate themselves deeply enough about the problem to be solved and got embarrassed one too many times presenting and defending half backed ideas. Maybe they lacked the skills to clearly communicate proposals to themselves and to their client.

The paradox that must be circumvented is that there is some contrivance in trying to be un-contrived. This is where certain practices are necessary to keep us artless, without our very honesty becoming a contrivance. Preparedness, capability, fluency, and sincerity are perhaps the most important.

Can we even be artless in a speculative design industry? It can be hard to be an artless graphic or fashion designer. The lack of more specific criteria pushes such pursuits into the slippery world of artfulness. It would appear that graphic designers in particular are often caught in between, a specific piece can be so light on criteria that it makes it difficult to hold up as design, yet it is still client criteria driven and thus not solely at the graphic designers discretion, the graphic designers can find themselves needing to present fairly arbitrary ideas as definitive in order to make a case for their design decisions. Architects might find this excessively flakey, furthering the prejudice of some that design is just a frivolous adornment tor rational decision making. Meanwhile, quantitative criteria sensitive engineers find most architects flakey.

I would suggest the existence of a continuum running from quantifiable certainty to qualitative flakiness, if you will. What we must do in this regard, in fact all we can do, is to identify all the criteria as well as possible. Graphic design will never be completely quantifiable, but by no means is it completely without criteria. Conversely, engineering is likely not quite so precise and conclusive as some would believe. In most design fields, intellectual depth is in the mind of the beholders.

Author:Scott Lockard

熱門頭條新聞

- 2025 Edition: Hungary, music video and an anniversary!

- SONY and Kadokawa Group have strengthened their collaboration to maximize their intellectual property

- QUByte Unveils Dark and Nostalgic Adventures for Consoles and PC

- OIAF2025

- Once Human Launching Three New Scenarios & Mobile Version In 2025

- ‘Memoir of A Snail’ to Open Anima Festival 2025

- New STALCRAFT: X Game Mode Revealed in New Trailer Showcased at The Game Awards

- Can CD Projekt Recapture the Magic?