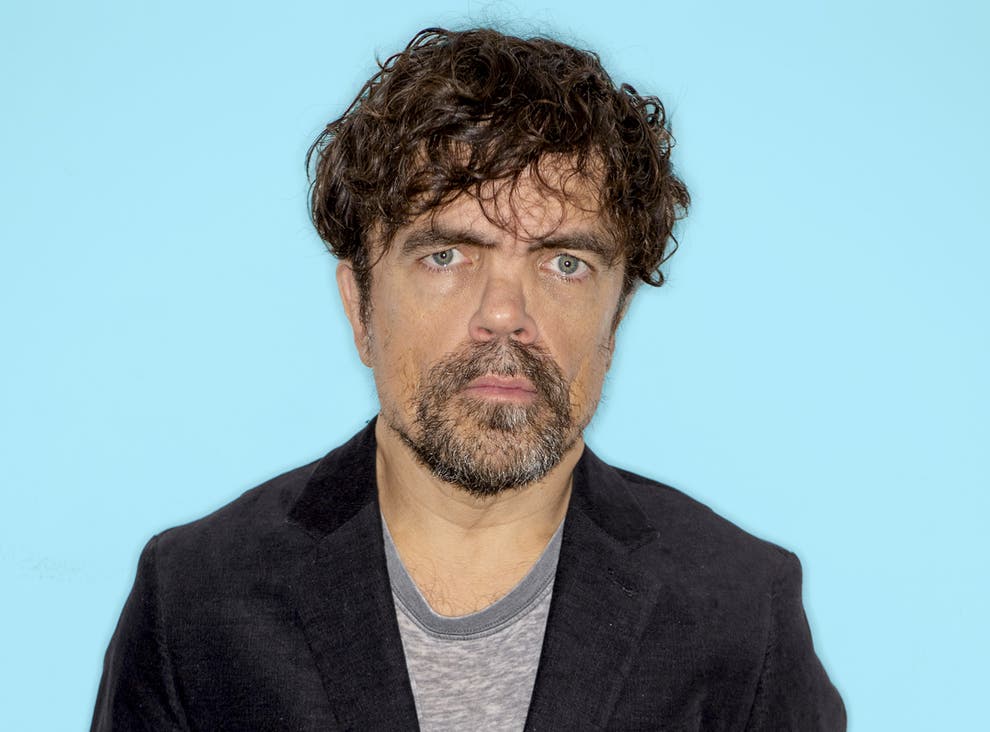

Peter Dinklage: ‘I would like to see some sort of gremlin get in the internet and shut the whole thing down’

After you’ve played Tyrion, everyone wants you to play Tyrion,” says Peter Dinklage. “Or a version of him. And that’s what you shouldn’t be doing. I never want to repeat myself: part of the fun of acting is getting to be somebody different each time.”

Still, you can see why they might ask. Over eight series and eight years, Dinklage’s performance as the brilliant dwarf prince Tyrion Lannister in HBO’s fantasy saga Game of Thrones made him globally famous. Shunned by his father for his stature, and for the death of his mother in giving birth to him, Tyrion was the show’s emotional centre: ingenious, brave, romantic, witty, cunning and drunk, often several of these things at the same time. It was the role of a lifetime, for which Dinklage won four primetime Emmys and a Golden Globe, and it opened every door in entertainment. But it was also the kind of performance that can have an inescapable gravity for an actor who isn’t careful about what they do next.

Since the end of Thrones in 2019, Dinklage has gone to great lengths to diversify. There was Martin McDonagh’s Best Picture-winning Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri; the post-apocalyptic romance I Think We’re Alone Now; a turn as a gangster in J Blakeson’s black comedy about guardianships, I Care a Lot. In between, there have been money jobs: a brace of Angry Birds, a Marvel spot in Avengers: Infinity War. Enough roles under the bridge, evidently, that he feels able to return to his most Tyrion-esque character since Thrones, as the lead in Cyrano, a new musical adaptation of Cyrano de Bergerac, out in the UK next month. Directed by Joe Wright, he of Darkest Hour and Atonement, it’s the film version of a 2019 Broadway play in which Dinklage also starred, written by Erica Schmidt. Her version is based on the original play, written by 1897 by Edmond Rostand, which fictionalises the real-life story of a 17th-century French writer and duellist.

“Erica Schmidt, our brilliant adapter and screenwriter, was commissioned to write a stage version of Cyrano de Bergerac,” Dinklage explains. “But the original is quite long, and it was written 120 years ago when people didn’t have the internet and didn’t mind how long they spent in the theatre. We’re more distracted now. Erica stripped it down to its bare essentials, took the monologues about love and turned them into love songs.” For the lyrics and music, she recruited musicians from the indie-rock band The National, whom Dinklage discovered after hearing them in a Game of Thrones make-up trailer in Northern Ireland. “I told Erica to listen to them, because they sing about love and heartbreak, and they are such Renaissance men that they threw themselves into the project wholeheartedly.”

Dinklage has flown to London (“probably my favourite city in the world”) for the publicity run, but the looming spectre of Omicron before Christmas means we are Zooming from rooms three miles apart. Now a youthful 52, he has been in the game for 30 years, and is friendly but guarded beneath his familiarly craggy features. He is being very faintly disingenuous in referring to Schmidt as though she were merely a professional collaborator: she is also his wife, and mother to their two children.

“Yes, she’s my partner in love,” he concedes. “We’ve worked together on a number of things before. I love working with her. I hope she can say the same about me. It’s difficult being married to an actor, I know.”

Schmidt was taking on one of theatre’s classic romantic comedies. In the original, Cyrano is in love with the beautiful and aristocratic Roxanne, but insecure about his physical appearance because of his big nose. With pen in hand, he is as passionate and persuasive as they come, and writes letters on behalf of the handsome but inarticulate Christian, with whom Roxanne is in love. The story has been adapted countless times: it was a memorable outing for Gerard Depardieu’s iconic schnoz, and the basis for Steve Martin’s Roxanne. In 2019 Jamie Lloyd redid it as a rap battle, with James McAvoy in the lead.

Nasal references have been excised from the new version. The audience might be tempted to think Dinklage’s stature casts him as the outsider, an idea the actor refutes.

“A lot of people think my height is the reason Cyrano is insecure about showing his love to Roxanne, but it really isn’t,” says Dinklage, who has spent a lifetime answering questions about his physical condition. “It’s more universal than a nose or whether someone is shorter than someone else. It’s that feeling we have of being unworthy of love and insecure about who we are.”

He says the part was not written with him in mind, but once he had performed it during a read-through at the couple’s home in New York, he was determined to play it. “I was like a bulldog,” he says. “I weaselled my way in.” His Cyrano is a quick-witted swashbuckler, less confident in love than Tyrion but making up for it in his ability to “kick some ass”, as Dinklage puts it. It’s a pleasant surprise to hear him open the pipes, too. “I can hit a note but would never describe myself as a ‘singer’,” he says. “You have to know when to fold.”

The story resonates in an era when everyone hides behind an online persona, sending messages that may or may not be an honest reflection of our selves. Although Cyrano might claim he is acting for noble romantic reasons, the plot, in which two men collude to trick a woman into loving them, is not unproblematic. “Basically [Cyrano] is catfishing, using Christian as his fake profile to get the girl. That’s what people do all the time now.”

Does he worry about his own children in this era? He and Schmidt have been protective of their offspring’s identities, to the point of not confirming either child’s name, or even the gender of their second, born in 2017 – a daughter was born in 2011. “Hopefully when my children are old enough to have all that maybe everyone will be a Luddite again,” he says. “I would like to see some sort of gremlin get in there and shut the whole thing down, so we go back to writing letters again. But I don’t think it’s going to happen.”

One question for Dinklage, now that he has such a wide choice of leading roles, is how to play his height. He has spent most of his career dodging the obvious stereotypes. After an upper-middle class childhood in New Jersey, the privately educated son of an insurance salesman father and a music teacher mother, he struggled to break through after drama school. Before Game of Thrones came along, he was offered all kinds of diminutive fantastical figures, “elves or leprechauns” in his words, but turned them down in the hope of building a more interesting career.

“I’m always taken aback by these very professional young people in my business who seem to have it all figured out,” he says. “I was a bit of a mess. I spent too much time thinking I was Jack Kerouac but not writing like Jack Kerouac. I guess in your twenties you’re supposed to be doing that, working out what you don’t want to do any more – like smoking – but making a lot of mistakes and learning from them. I got more serious in my late twenties.”

Still, bills have always had to be paid. His breakthrough performance in Tom McCarthy’s brilliant The Station Agent came in the same year, 2003, as perhaps Dinklage’s most controversial film, the straight-to-DVD Tiptoes, in which Gary Oldman played a man with dwarfism.

“[Thrones’ success] does afford you the luxury of being able to be more particular about what you do,” he says. “There are jobs you take, and maybe later wish you hadn’t, but no regrets, it’s work, and we’re all lucky to be working.” He has made a point of never putting himself forward as a spokesman for his condition, but is happy if he has helped others in a similar situation. “I never want to put myself in front of the work, and I never will,” he says. “But if I’ve done my job and inspired change, then great.

“I read a lot of scripts where the height is the only characteristic of the character, but that’s not who I am,” he adds. “It’s part of who I am, but I don’t go around thinking about it all day long. And if it doesn’t define me, why should it define a character? That’s just bad writing.”

While Dinklage has moved on from Westeros, the Game of Thrones universe may be just beginning. HBO is working on House of the Dragon, a prequel set 300 years before the events of the original TV series, set to air later this year. “I think the trick is not to try to recreate Thrones,” he says. “If you try to recreate it, that feels like a money grab. With a lot of sequels, the reason for them is that the first one made a lot of money, which is why they aren’t as strong. But I am excited to watch the House of the Dragon, purely as a viewer, not knowing what will happen next.”

Many viewers were furious with the finale of Game of Thrones, in which the putative heroine Daenerys Targaryen turned genocidal. “People were just mad because nobody wanted it to be over,” Dinklage says of the outcry. “I know a lot of people were supposedly surprised by the ending, but if you paid attention, the clues were there. We told you not to name your dog Khaleesi.”

After Cyrano, he says he has “cleared the slate” to spend some time with his family. Beyond that, he hopes to do more directing and producing, to “get up a bit later in the day”.

Source:Independent

熱門頭條新聞

- INTERVIEW: The Winning Formula For “Plankton: The Movie”

- Submissions for 2025 Annecy VR Works Are Open

- ‘Rudy – The Prophecy of the Flying Boy’ Belgian Animation Feature in Development

- Purple Brain Production

- NetEase Games’ Subject Matter Experts to Present Tech Talks at GDC 2025

- Autodesk announces a workforce reduction

- Swedish Methods for Gender Equality Driving Change in the Games Industry

- Jagex announces CEO Transition